Tiny fragments come together to shine a little extra light on the lives of an ‘ordinary’ family in Ancient Egypt three thousand years ago.

by Nigel Fletcher-Jones

Three thousand years ago, a scribe sitting near the village of Deir al-Medina — across the hill from the Valley of the Kings — picked up a stone and wrote rapidly across it in the shorthand script used every day for administration.

When, in the twentieth century, an archaeologist picked up that stone, I like to think there was a frisson of excitement on his or her part. What might it say? What new clues might it reveal about ancient Egypt, and the man — or, perhaps, woman — who had written the text?

The answer would have to wait, of course, until one of the very few experts who could decipher the shorthand, known as hieratic, had time to look at it.

I like to imagine all the speculation that might have gone on, until one day a letter arrived from the expert revealing the secret that had survived through the millennia. Breathlessly, the recipient would open the envelope, unfold the letter, scan through the greetings, until he or she reached the line, ‘It says, “Another small stone.”

Welcome to the wonderful world of ostraca! A single ostracon, in a general archaeological context, is a fragment of flat stone or pottery upon which someone had written something.

Thousands of these limestone and pottery fragments, together with pieces of papyrus, have been recovered from the workmens’ village of Deir al-Medina, which was home to the craftsmen who created the New Kingdom tombs in the nearby valley. These ephemera — notes on law cases, messages, spells, and the like — give us a particular insight into the characteristics of an ancient Egyptian village, though not necessarily an entirely representative one, as the inhabitants of Deir al-Medina were probably more literate than their neighbors, by virtue of their work.

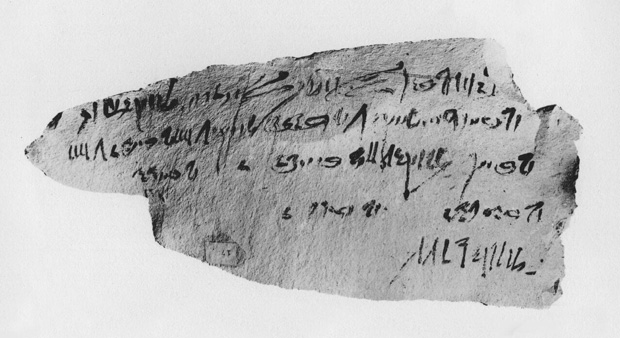

An ostracon and Qenhirkhopshef’s handwriting (from Mrs. Naunakhte (AUC Press))[/caption]

An ostracon and Qenhirkhopshef’s handwriting (from Mrs. Naunakhte (AUC Press))[/caption]

There is so much detail to be gleaned from these sources, by those few who can read them, that it is able to shed light on some of the most obscure individuals in ancient history.

In his new book, Mrs. Naunakhte & Family: The Women of Ramesside Deir al-Medina, Koenraad Donker van Heel does some impressive jig-saw puzzle work with ostraca to explore the life and times of an ‘average’ woman in Deir al-Medina.

Perhaps understandably in a village of workmen gathered together for their special talents, exploring the life of a woman in Deir al-Medina is particularly hard. Yet, it is probable that women had great influence in everyday life, not least because the men were away in the Valley of the Kings for most of the ten-day week.

Some women could likely read and write—they did, certainly, send messages to each other by ostraca. Some managed the work in the fields towards the river. Some were landowners in other villages.

The houses of Deir al-Medina (image courtesy of Kate Gingell)[/caption]

The houses of Deir al-Medina (image courtesy of Kate Gingell)[/caption]

Naunakhte may not have been so ‘average’, in any case. She certainly lived into old age, even by modern standards. Her first marriage was to the senior scribe of the village, and she probably taught at least some of her children to read and write. She also had personal status as a singer of Amun—a member of the group of musicians and singers who would accompany priests in rituals.

Furthermore, we have a great advantage in exploring the life of Naunakhte because her will has survived.

It consists of four papyri possibly discovered together in 1928. The will was written around 1142 BC, during the reign of Ramesses V, and toward the end of her long life—she was probably approaching eighty at the time.

The will tells us that she had eight surviving children from her second marriage to a workman named Khaemnun, but not all of them would inherit from her upon her death.

Amongst the property to be inherited there was a storeroom that belonged to her father; property—including an extensive library—which she had inherited from her first husband, the scribe Qenhirkhopshef; and property acquired jointly by Naunakhte and her second husband, Khaemnun, of which, by law, one-third was hers to distribute.

There is something of an air of disappointment pervading the will with regard to some of her children, for some had clearly been too busy or too lacking in care or too lackadaisical to help provide for her in her old age.

Two daughters would not inherit a part of Naunakhte’s wealth acquired from her first marriage for this reason, and one son, who wasn’t named, presumably because everyone present knew he was a bit of a wastrel, also received nothing. (One daughter may also have received less because she was sleeping with another man, earning the wrath of her elderly mother.)

However, one son, named Qenhirkhopshef after Naunakhte’s first husband, received an extra share, and also inherited the family library. Perhaps he was the first-born son.

Both from the will itself and from the wealth of detail that can be extracted from ostraca, we can begin to reconstruct Naunakhte’s life and those of her husbands and children.

Her first husband had become senior scribe by around the year 1240 BC under Ramesses II, but it was not until circa 1210 BC that he married Naunakhte. He was about 50 and she was probably around 12 – not an unusual occurrence in ancient Egypt, though Qenhirkhopshef would have already outlived many of his contemporaries by then.

The couple lived in a house in the northeast of the village, which had belonged to Qenhirkhopshef’s adoptive parents, the senior scribe Ramose, and his wife, Mutemwia. We do not know whether they had children, but, if they did, they did not survive. None the less, it seems to have been a sufficiently happy marriage that, later, Naunakhte and her second husband named a son after Qenhirkhopshef.

Deir al-Medina at street level (image courtesy of Paula Veiga)[/caption]

Deir al-Medina at street level (image courtesy of Paula Veiga)[/caption]

It is probable that the senior scribe adopted his wife, thus clearing the way for her to inherit all of his estate, and, particularly, his library.

Perhaps his greatest gift, however, was that he appears to have taught his young wife to read and write. This was a gift that considerably raised the status of Naunakhte’s later family in the village, not least because it is likely that she taught her children to read and write too. Her sons certainly were not only workers, but also carpenters and scribes in their spare time.

Qenhirkhopshef the elder probably died at some point in the reign of Seti II (approximately 1200—1194 BC), and it is probable that Naunakhte married Khaemnun—a senior workman—soon afterwards (she would not have been allowed to stay in the village for any length of time otherwise—a house in the village was state property).

Upon her death, presumably soon after 1142, Qenhirkhopshef’s library passed to Naunakhte’s son, Qenhirkhopshef, and from him to another son, Maanimakhtef.

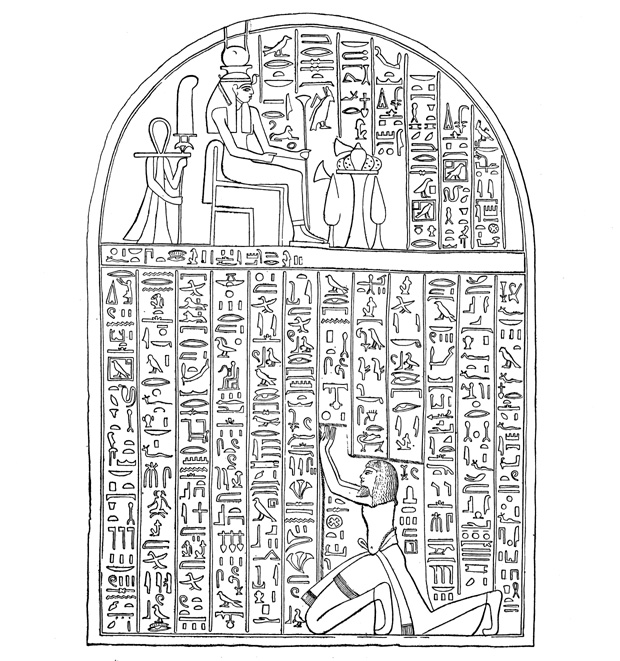

The stela of Qenhirkhopshef, son of Naunakhte and Khaemnun (from Mrs. Naunakhte (AUC Press))[/caption]

The stela of Qenhirkhopshef, son of Naunakhte and Khaemnun (from Mrs. Naunakhte (AUC Press))[/caption]

It is likely that this library contained several important literary works, and it would have been a happy end to this story if they had survived to this day.

Sadly, however, Maaninakhitef—a carpenter—loved to write letters, and appears to have fairly systematically cannibalized the literary papyri when he needed material for his business letters. Traces of the original texts were erased from his letters, and strips cut out of other papyri. Thus, the original texts were lost forever.

A sad end to the tale, but even so, the curious case of Mrs. Naunakhte and the ostraca illustrates beautifully how, in the absence of biography, the tiniest fragments can be joined together to shine a little extra light on the lives of an ‘ordinary’ family three thousand years ago.

Nigel Fletcher-Jones is director of the American University in Cairo Press. Join Nigel on Facebook and browse AUC’s list of stores at aucpress.com.

Comments

Leave a Comment