by Nigel Fletcher-Jones

As dusk settles over modern Luxor, and from the very top of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, it is possible — as it was in antiquity — to make out the outline of the great temple of Karnak across the Nile.

Look down from that vantage point, on a line towards the modern visitors’ centre, and you will also see a rather unprepossessing low square of wall—unlabeled and ignored by the passing tourists and local people alike.

Peering inside this enclosure—known as Bab el-Gasus (‘the gate of the priests’) — is not very enlightening, yet this is the entrance to the last resting place of 153 priests and priestesses who served the god Amun in that temple across the river during the 21st Dynasty (around 1070–945 BC).

[caption id="attachment_514450" align="alignnone" width="620"] The location of the Bab el-Gasus at Deir El-Bahari (courtesy Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

The location of the Bab el-Gasus at Deir El-Bahari (courtesy Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

Now virtually unknown to visitors and little considered by many Egyptologists, the tomb caused something of a sensation when it was discovered in 1891. The sheer scale of the discovered assemblage rivals the most famous collections, including that of Tutankhamun. In an excavation so short—a matter of days—that it would make any modern archaeologist sob uncontrollably, out of that hole and the long corridors and burial chambers, which cross the temple enclosure some seventy feet below, came 254 exquisite coffins (101 double sets), 110 boxes of shabtis, nearly 100 papyri, 80 statuettes, stelae, amulets, textiles, and even flowers.

[caption id="attachment_514453" align="alignnone" width="620"] Double coffin of Khonsumose, Medelhavsmusee, Uppsala (courtesy Aidan Dodson)[/caption]

Double coffin of Khonsumose, Medelhavsmusee, Uppsala (courtesy Aidan Dodson)[/caption]

Egypt had entered four centuries of decline and upheaval following the murder of Rameses III a few decades before the 21st Dynasty began, during which successive ‘national’ pharaohs ruled from Tanis in the Delta, but High Priests of the Temple of Amun at Thebes effectively ruled Middle and Upper Egypt. Thus, the finds in Bab el-Gasus provide a unique window into a turbulent time, and demonstrate to a considerable degree how men and women of the middle levels of society lived and died.

Yet, at a recent conference held at the Ministry of Antiquities in Zamalek to mark the 125th anniversary of the excavation, Bab el-Gasus was referred to as ‘the forgotten discovery’. How could this have happened?

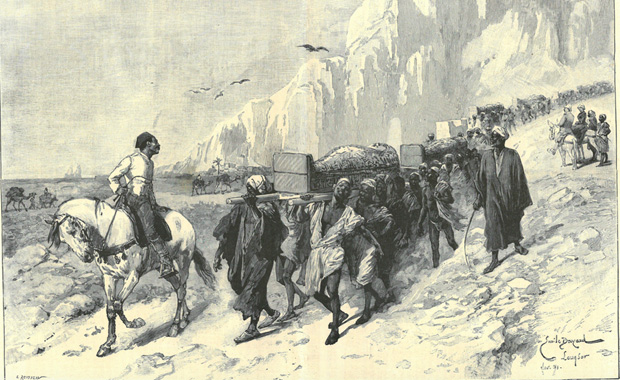

It seems that, to a great extent, the excavation of Bab el-Gasus was a victim of its own success. The long procession of objects brought out of the tomb so overwhelmed the Gizeh museum—the predecessor of today’s Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, that the Egyptian Khedival government decided in 1893 to give half of the coffin sets and a few other pieces away to western countries. Some of these lots were further sub-divided upon arrival: in France a number of regional museums thus received material via the Louvre. Record keeping was, to say the least, a little vague at times.

[caption id="attachment_514451" align="alignnone" width="620"] The clearance of the tomb, Emile Bayard, L’illustration, 4th April 1891 (courtesy Cynthia Sheikholeslami)[/caption]

The clearance of the tomb, Emile Bayard, L’illustration, 4th April 1891 (courtesy Cynthia Sheikholeslami)[/caption]

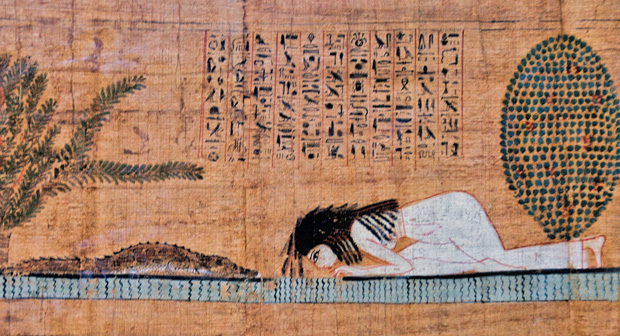

Many of the coffins that remained in Egypt found their ways into storage rooms from which few have subsequently emerged. Even some of the remarkable papyri — such as the lovely example of the woman and the crocodile belonging to Herweben — hang rather forlornly in the stairwells of the Egyptian Museum today without a mention of where they came from.

[caption id="attachment_514454" align="alignnone" width="620"] Woman and Crocodile papyrus detail (courtesy Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

Woman and Crocodile papyrus detail (courtesy Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

Yet, in the thirty or so museums abroad where the coffins are to be found, their jewel-like qualities often make them a central part of the Egyptology collection. They are recognizable by the deep yellow varnish applied by the craftsmen of the Theban coffin workshops. The complexity and beauty of the decoration seems to belie the turbulent time in which they were created, but those characteristics in themselves are symptomatic of the changed times. It was no longer possible to prepare the richly decorated tombs of the New Kingdom. The Ramesside pharaohs had been the last to be buried in the Valley of the Kings. The decoration of the sides, floor and lid of the coffin became a substitute for the walls and ceiling of the tomb, and new elements formerly found in the royal tombs were incorporated.

While Bab el-Gasus may have been forgotten by many Egyptologists, over the years there has been a small, but steady, stream of academic publications on the finds. From these has come a dawning realization that concerted detective work could reunite – at least on paper — the now-scattered parts, and allow us to draw more general conclusions about the lives of the men and women who found rest in Bab el-Gasus.

Indeed, one of the most fascinating elements in this rediscovery process has been that it has allowed closer scrutiny of the role of women in the religious practices of the period. Seventy high-status women — chantresses of Amun — have been identified from the finds, and research is ongoing into their family relationships and the meaning of their various titles.

In this 125th year since its discovery, then, it appears that Bab el-Gasus is finally coming out of the shadows and into the limelight it deserves. A further conference on the site has been announced for September 19-20th in Lisbon.

If sufficient funding can be found, it is also likely that there will be a special exhibition on Bab el-Gasus at the Egyptian Museum in November which will draw together some of the key pieces for the first time. That would be something to see!

(With special thanks to Cynthia Sheikholeslami and Aidan Dodson.)

Nigel Fletcher-Jones is director of the American University in Cairo Press. Join Nigel on Facebook here and browse the AUC Press website here.

Comments

Leave a Comment