Recording natural history can sometimes be an unpalatable process

By Richard Hoath

M y piece last month was glamorous. We went from the oak- and pine-infused mountain forests of the Moroccan High Atlas to the riparian riches of southern Africa’s Malawi. And then back to Egypt’s Eastern Desert before exploring below the sublime waters of the Red Sea. And the wildlife, all alive and thriving – Barbary Macaques, African Bushbucks, Dorcas Gazelles and slumbering parrotfish. Wonderful places and wonderful creatures. But natural history is not always so alive (if asleep) or exotic. Far more often it is grittier, un-exotic and urban — and in a way just as fascinating.

On January 23, I was walking home from a shopping sojourn in the mega-urban environs of Garden City. The usual suspects were there, House Sparrows, Common Bulbuls and Palm Doves. And a weasel. Weasels are common in Garden City: a tiny, furry cylinder of a mammal, and an active predator to boot, that is most often seen dashing between parked cars in the early morning. I see it regularly here, as do many friends and colleagues in Zamalek, Heliopolis, Maadi and elsewhere.

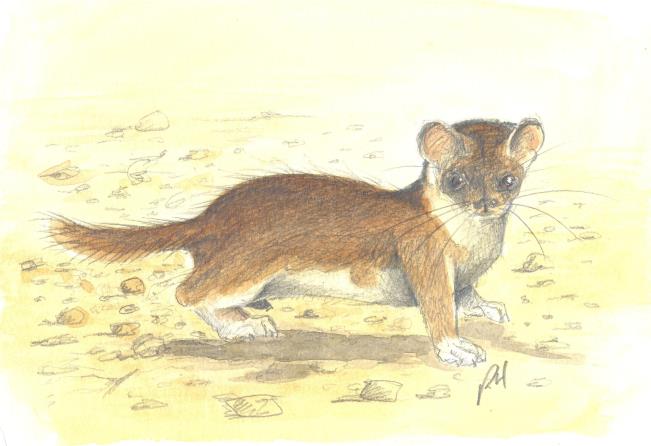

This is interesting in itself as the Egyptian weasel (no capital) is an almost entirely urban mammal in this country. Elsewhere — and it has an enormous range over much of temperate Asia, Europe and North America as well as North Africa — it is a creature of the countryside. Here it is a city dweller, restricted largely to Cairo with isolated records from parts of the Delta and Fayoum. The weasel of Egypt was previously treated as a subspecies of that cosmopolitan Common Weasel, in scientific lingo Mustela nivalis subpalmata. In recent years, this subspecies has been elevated to species level Mustela subpalmata first described by the distinguished naturalists Wilhelm Hemprich and Christian Gottfried Ehrenberg in 1833. This is the Egyptian Weasel, now capitalized.

My Egyptian Weasel, as we are being gritty and un-exotic, was dead. Very recently dead. And as a naturalist I had little option but to collect it. To the utter amazement and bemusement of those thronging Garden City’s convoluted streets, I plucked my specimen from the pavement, wrapped it in a recently purchased state-owned newspaper (perhaps appropriate), and strode back to my building.

Back at home I did what naturalists do. I photographed my Egyptian Weasel with close-ups of the head and hind limbs, and with a ruler and, my favorite, a Bic biro for scale. The dark chestnut upperparts and pale underparts were clear, but the two were not clearly demarcated as in most Common Weasels, and there was extensive blotching on the chest and belly typical of subpalmata. I measured it for all the important parameters: head and body length, tail length, hindfoot length and various ear measurements. It was very definitely a male as the definitive bits were very much there, and it seemed a healthy and robust individual. It had certainly not starved.

Recording done, it went into the freezer. It is now with the Biology Department of the American University in Cairo. And it could be a record breaker.

My weasel is huge. Its head and body length is 315mm, 6mm longer than the longest record from Osborn and Helmy’s definitive The Contemporary Land Mammals of Egypt (Including Sinai). Its total length of 315mm plus 143mm of tail (by my maths 458mm) is way beyond the 360mm recorded by Harrison and Bates in The Mammals of Arabia. It is substantially bigger than the largest specimen recorded in Macdonald and Barrett’s Mammals of Britain and Europe (314mm head and body) and fractionally bigger than the longest recorded in Aulagnier et al Mammals of Europe, North Africa and the Middle East (430mm). I have, or AUC’s freezer has, a mega-weasel.

It could of course be a one-off, a freak. But it could also be an indication that as in other commensal mammals such as the Brown Rat and the House Mouse, urban populations are larger than their rural counterparts. Perhaps it is diet. Hopefully an analysis of the stomach contents may show exactly what our urban weasels are feeding on. A chance encounter with a dead weasel could lead to a deeper understanding of a mammal only recently accepted as a full species.

If picking up deceased mustelids from crowded sidewalks is not embarrassing enough, my mind goes back some years to when I was researching my Field Guide to the Mammals of Egypt. I was in Harpenden, the charmingly sleepy, suburban village where I was born, about 40 miles north of London. My parents still live there, and I was visiting. By happy chance the headquarters of the Cat Survival Trust is very close by in the village of Codicote. This organization, of which I am an official Friend and active supporter, rescues wild cats from the illegal pet trade and from zoos and collections that have been closed down, and either re-houses them or provides them with sanctuary. They have had in their care Amur Leopards and Snow Leopards, Pallas’ Cats and Bobcats, Servals and Ocelots and more. And they have had Caracals.

The Caracal is a cat of the desert and savannah, larger than the domestic cat and weighing in at up to 18 kilograms. It is uniformly beige to tan, paler beneath, with a short tail and very long ear tufts, with ears distinctly black behind. In Egypt it is very elusive indeed, with records from the Sinai and the Eastern Desert. Its present status is uncertain.

But with a book to write and plates to paint, the chance of close encounters with Caracals in Codicote was too good an opportunity to miss. I visited the cats and was able to draw and sketch them from life. They are beautiful. While many of the larger wild cat species are elaborately spotted or striped or maned, the Caracal is unpatterned, but the ears are so expressive and the face subtly but dramatically marked in black and white. I watched and sketched in conditions as close to natural as I could realistically expect. And at the end of the sessions, the curator gave me a very precious package: a bag of Caracal poo.

Mammals are elusive. Mammal researchers in the field may only get very fleeting glimpses of their subjects and often rely on secondary means of studying their quarry. This may be high-tech gadgetry such as infrared cameras or camera traps. But it may also be more down to earth, quite literally, in the animal’s tracks, trails and spoor. Their poo, their droppings, their excrement — there is no polite way to say it. So the chance to photograph Caracal poo as a reference for subsequent desert trips — where I stood virtually zero chance of seeing the actual animal, the pooer as it were —was too good to pass up.

I took my precious package back to genteel Harpenden and on my parents’ patio I laid out sheets of white paper on the paving. Taking my ruler for scale and that Bic biro again, I set about arranging the pieces of poo as accurately and scientifically as I knew how. And then, camera in hand, I began to record for posterity the toilet products, a poo panorama, of one of the region’s least-known wild cats.

It was at that moment that the porch doors opened and my parents came through with a large posse of neighbors whom they had invited round for a quiet pot of afternoon tea. Quite what these cultured suburbanites made of this I will never know, but the look on their faces was much the same as on those of Garden City passers-by seeing someone very gently and carefully gather a dead weasel off the tarmac. All in the cause of natural history. et

Comments

Leave a Comment