By Richard Hoath

After a summer of discontent with events of huge significance happening on an almost daily basis it can be good to find solace in the smaller things in life. And thus last month a chance discovery on a walk to work led to an all too infrequent encounter with one of Egypt’s most iconic creatures and to a minor epiphany – I fell in... well, at least in like with my new smartphone.

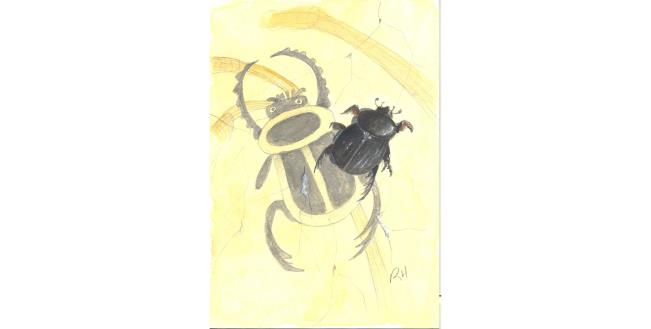

The creature in question was a robust beetle sprawled upside down and kicking substantial legs in a slow, mechanical and futile attempt to right itself. How it had arrived thus on a pavement in New Cairo is uncertain — perhaps dropped by a Kestrel or a predatory Southern Grey Shrike, both of which have colonized this new mega-suburb. Having righted the beetle I realized that what I had was a scarab. Out came the smartphone and with a swipe and a click, a fiddle and a dab, the animal was photographed and its image sent to an entomologist friend in the United States (who had spent many years working here). Before long I had an ID; it was as I had expected a beetle of the family Scarabaeidae. It was a scarab.

My smartphone had come up trumps. I had replaced my ancient, clunky museum piece of a mobile after my sojourn to Cameroon this summer. Outside the cathedral of Douala, the regional capital, those waiting for alms or begging for small change all had better phones than I. Now my new toy, purchased out of embarrassment rather than need, had come up trumps. I have yet to embrace the brave new world of apps and androids, but if I can get a beetle ID in the time it takes to prod a few buttons, then I am on my way to conversion.

I shared the phone picture with some friends and colleagues. One, a distinguished Egyptologist, was as excited as myself, but the general reaction was a shrug, a pseudo display of mild enthusiasm or just “Ughh! It’s a bug.”

But it was not just a “bug.” For a start, the term “bug” is a generic term in the US for any insect. The true bugs are insects of the order Hemiptera, characterized by piercing mouth-parts and overlapping elytra or wing-cases. My “bug” was not a true bug but a beetle — and not just any beetle, a scarab.

Few animals are as closely associated with Ancient Egypt as the scarab and more especially the Sacred Scarab Scarabaeus sacer. A member of the Scarabaeidae, this is a heavy bodied bulldozer of a beetle some 2cm long and almost as broad. It is glossy black in color with a slightly ridged carapace. The species is distinctive for the structure of the front legs which lack a “foot” and which are ornamented with four blunt spines, and for the front of the head bearing six prominent projections. The Ancient Egyptians portrayed these details many times with stunning accuracy, such as in a portrayal of a large scarab in the tomb of Inherkha from the Twentieth Dynasty at Thebes and reproduced in Patrick Houlihan’s The Animal World of the Pharaohs. But it too appears in the zillions of reproduction amulets available from every tourist outlet in every tourist center. The Sacred Scarab is synonymous with Ancient Egypt. But why?

The Scared Scarab is one of a group of scarabs known as dung beetles. The beetle either singly or in pairs rolls a ball of fresh dung, pushing it along with the heavy hind legs. At a suitable spot the ball is buried either to be eaten safely underground or, and accounts vary, to have an egg laid in it by the female. When the egg hatches the beetle larva dine on dung and after further metamorphosis emerge as an adult beetle. Other authors describe the female creating a separate pear-shaped ball underground in which the eggs are laid.

For the Ancients this process had double significance. Firstly the rolling of the dung ball was seen as analogous with the rolling of the sun across the sky from east to west, and the Sacred Scarab was thus associated with the daily rebirth of the life-giving sun. Secondly, but closely related, the emergence of the fresh insects from their natal dung ball was seen as their spontaneous rebirth or creation. Thus the humble Sacred Scarab, all 2cm of it, became intimately associated with the god of the morning sun Khepri – a manifestation of the sun god Ra. And this association was a vastly long one from the Old Kingdom dynasties right through to the Greco-Roman period. The beetles were even wrapped, mummified and placed in decorated sarcophagi, while their amulets were used as stamps and seals, as jewelry or as funerary objects planted in the mummy wrappings.

Today the Sacred Scarab along with its dung beetle relatives still performs the important function of fertilizing the soil, returning the nutrients provided in the animal dung to the humus. Houlihan reports them as a common sight in the countryside but my best scarab site has to be the Visitor’s Center at Zaranik in North Sinai. There on the desert coast the porch lights attracted a myriad moths, crickets and grasshoppers and amongst them, the clunking tank-like forms of big beetles, of scarabs.

In the city there are big beetles too but generally of a different family. The nocturnal ground beetles or darkling beetles of the family Tenebrionidae are found at night even in central Cairo. They can be as large as the scarabs but are more elongated with much longer unornamented legs and a smooth, matte carapace.

Images of any of these species can be found searching Google Image — but be warned. Last summer my parents found a perfectly spherical hole in their lawn, large but too small to be made by a mammal and with no evidence of any external burrowing or disturbance. I identified it as the emergence hole of a large species of British beetle. The female lays her egg underground, the larva develops feeding not on dung, but on plant roots, making something of a pest of itself in the process. In late summer the adult beetle emerges, and it is an impressive insect. I recommended they Google the image and gave them the beetle’s name. Do not ask your parents to Google “Cockchafer.”

My beetle, while undoubtedly a scarab, was not a Sacred Scarab as it lacked the ornamentation to the head and forelimbs and the latter appeared to bear tarsi or foot segments. But the structure of the latter two pairs of legs, strong, rather flattened and ornamented, indicate that its habits would be similar to those of the Sacred Scarab. I may never know the exact species since there are more species of beetle in the world than any other type of animal. Over 400,000 species, by one estimation one third of all animal species, have been described to date and the number is constantly growing. My new smartphone is smart but not that smart. et

Comments

Leave a Comment