Gayer-Anderson, mostly known for the ancient cat that was once in his collection, led a fascinating life as an adventurer, surgeon, soldier, collector, dilettante, and lover and preserver of beauty.

all images from Gayer-Anderson: The Life and Afterlife of the Irish Pasha (AUC Press)

One of the most beloved objects on display in the British Museum is a bronze figure representing the goddess Bastet. It stands 14cm high and takes the form of a seated cat with incised details, an inlaid silver sun-disc, a wedjat-eye pectoral ornament, and gold earrings and a nose ring.

Modern copies of this famous cat have been bestselling items for the British Museum shop for many years, but the original was probably created in the Late Period (perhaps around 600 B.C.) in Memphis.

Like many such objects found in the world’s museums, the cat bears a name that, on the face of it, bears no relationship to the ancient origins of the piece. It is known simply as the Gayer-Anderson Cat.

The Gayer-Anderson Cat[/caption]

The Gayer-Anderson Cat[/caption]

The life of the man behind the cat is explored in a new book, Gayer Anderson: The Life and Afterlife of the Irish Pasha, by Louise Foxcroft.

The future Major Robert Grenville Gayer-Anderson Pasha was born alongside an identical twin—with whom he had a mystical connection throughout his life—at Listowel, County Kerry on July 29th, 1881.

From his mother, he believed, he inherited the intense love of beauty that became the driving force of his life. That this love of beauty should become fixed principally on objects, however, may well be attributable to what Gayer-Anderson described as the “decided strain of sadism” exhibited by his father. Even by the standards of the age, the father was a martinet’s martinet, who rigidly suppressed the expression of emotion.

As a result, Gayer-Anderson learned to camouflage his feelings beneath the impenetrable armor of ritualistic behavior and excessive orderliness, and, even during his school years, he became increasingly obsessed exclusively by the power of beauty and the acquisition of beautiful things.

At the age of seventeen, in 1898, Gayer-Anderson started medical training at Guy’s Hospital in London, emerging as a qualified surgeon 5 years later. His experiences in the hospital challenged him to think deeply about the meaning of life, and resulted in a lifelong development of a personal belief system associated with the paranormal and solitude.

Forever a restless spirit, Gayer-Anderson followed his twin brother in 1904 into a military career, albeit within the Royal Army Medical Corps. After training, he was seconded to the Egyptian Army as bimbashi (major) in 1907, practising as a surgeon in Abbasiya.

Gayer-Anderson (left) with his twin brother, Tom (Cairo,1912).[/caption]

Gayer-Anderson (left) with his twin brother, Tom (Cairo,1912).[/caption]

Immediately intoxicated by the sights and sounds of Cairo—to a far greater extent than most of his British officer colleagues—Gayer-Anderson set about learning Arabic and the customs of Egypt. Unsurprisingly, it was not long before the desire to collect beautiful objects took hold of him and, armed with passable Arabic, he began to make contact and develop friendships with Luxor antique dealers.

In the Season then, Cairo came alive with the smart-set of American and British tourists wanting to immerse themselves in the fad of Egyptology that had been ignited in part by the work of Flinders Petrie in Giza, and the possibilities of this receptive market did not escape Gayer-Anderson.

As a recruiting officer for the Egyptian Army from 1912, he was able to travel widely, and simultaneously enhance his reputation as a collector and a dealer.

From around 1914 onwards, dealing in ancient Egyptian and Middle Eastern artifacts became his principal concern in life, much to the detriment of his official duties. He was especially adept at finding lovely objects, and taught himself to clean, repair and restore them, enhancing both their beauty and value spectacularly.

Oriental Secretary (1912).[/caption]

Oriental Secretary (1912).[/caption]

He believed that there were often psychic influences involved in the process of collecting, and that there was sometimes a telepathic link with objects that were in a state of distress due to neglect or danger of destruction. Yet while the mystical elements might beguile him, he remained distinctly pragmatic in both the buying and selling of the objects that called to him, and amassed large collections of all sorts. Poignantly, he described the individual pieces in his collection as his children, but many of them were destined to be sold, lucratively, to the larger museums in America, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia.

The Egypt of those years seems to have called particularly clearly to those who could not temperamentally or emotionally fit into the norms and strictures of their birth society. Gordon, Kitchener, and Lawrence come to mind—boy-men seeking adventures, who never entirely lost their connection to childhood.

Increasingly, Gayer-Anderson sought to live “à la mode orientale”, dressing—within the confines of his own apartment initially—in fine Arab clothes and jewelry. By 1920, he was Oriental liaison to the British residency, entertaining important Arab guests passing through Cairo dressed in khaki during the day, and “as a magnificent Arab” at night. Cairo had become completely his home, and there was by now little remaining attraction in returning to England.

In ‘Arab dress’. Beit al-Kretilya (1930s).[/caption]

In ‘Arab dress’. Beit al-Kretilya (1930s).[/caption]

When Fuad became king following Egyptian Independence in 1922, Gayer-Anderson accompanied him on a royal tour of the provinces, but he retired from the Egyptian Government in 1923, at the age of forty-two, to “commune with beauty”, concentrate on his antiques business, and write articles on artistic and archaeological subjects for magazines. He drove a hard bargain in his dealing, but still often undercut the well-known dealers, and each of the objects that he sold was guaranteed genuine.

The sources of some of these objects were questionable, however, perhaps none more so than that associated with the villainous “old friend” from Saqqara who arrived at Gayer-Anderson’s flat one day in October 1934 with a large bundle wrapped in cloth. Inside, of course, was the exceedingly rare and beautiful cat bronze which was to bear Gayer-Anderson’s name within the prized collection of the British Museum.

By the mid-1930s, Gayer-Anderson’s health was declining, and he began to contemplate returning to England, and to the Little Hall in Lavenham, which he had bought in 1924. Some of his collection was duly packed up and sent to Suffolk.

Yet there was one last twist in his love affair with Cairo.

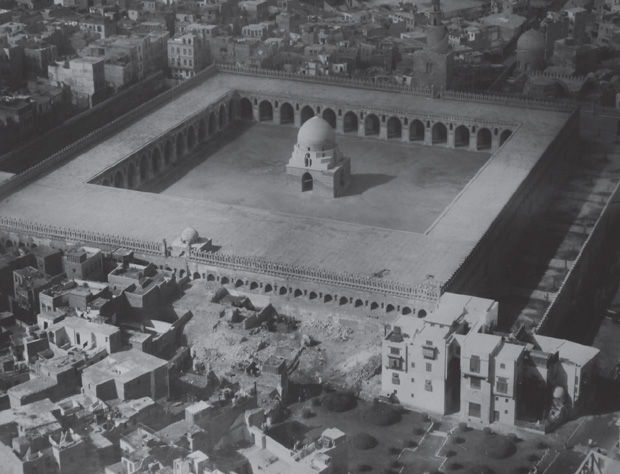

In February 1935, he visited the two sixteenth-century Mamluk buildings known as Beit al-Kretilya (“the House of the Cretan Woman”), which lay against the wall of the Ibn Tulun Mosque. He had first been drawn to the buildings as a young man in 1907, but now they called to him again. The buildings were in the process of being restored by the Comité de Conservation des Monuments Arabes, but a written application to the Comité secured the building for his lifetime. Much of his collection was to remain in the carefully restored rooms of the Gayer-Anderson Pasha Museum of Oriental Arts and Crafts when, in 1942, he returned to live permanently in Lavenham, and the museum can still be visited today.

Beit al_Kretilya (bottom right) and the Ibn Tulun Mosque (1935)[/caption]

Beit al_Kretilya (bottom right) and the Ibn Tulun Mosque (1935)[/caption]

One final honor was bestowed on this extraordinary man in 1943, when King Farouk made him a lewa (major-general) carrying the tile of pasha, and Gayer-Anderson made one last trip to Cairo in November 1944, to formally hand back the Beit al Kretilya and its treasures to the Egyptian people.

He arrived finally back in Lavenham in late May 1944, and died from a heart attack in June 1945.

Thus drew to a close one of the most fascinating lives—as adventurer, surgeon, soldier, collector, dilettante, and lover and preserver of beauty—of all those who have felt the call of Cairo.

Nigel Fletcher-Jones is director of the American University in Cairo Press. Join Nigel on Facebook and browse AUC's list of stores at aucpress.com.

Comments

Leave a Comment