Who were the mummies? While science is giving us more insight into the personality of ancient individuals, museums are also focusing their displays on the lives of those individuals - and not on their mummified remains.

by Nigel Fletcher-Jones

The older I get, the more uneasy I become about the public display of mummies.

As a trained archaeologist and biological anthropologist, I am more used to the excavation and handling of human remains than many people, and I recognize, of course, that the scientific evaluation of mummies has made us all a great deal more respectful even over my lifetime.

However, the ethical dilemma associated with the public display of mummies was brought home to me recently when, at a tourist museum, I saw a complete resin copy of the body of Tutankhamun, and couldn’t decide whether this was better or, in some manner, worse than viewing the real body in such a commercial setting. There was certainly very little, if any, scientific validity in this particular ‘exhibit’.

And therein lies the crux of a dilemma, for at an early age many children know at least three things about ancient Egypt: pyramids, hieroglyphs, and mummies, and, for a remarkable number of those children, ancient Egypt will remain a fascination for life, and the mummy a central plank of that fascination.

The dilemma is not lost on museum curators, and there is an increasing interest in deflecting attention from the mummies themselves toward the context in which they were found, and what it may tell us about the life of those individuals.

The forthcoming re-organized display of the royal mummies at the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Fustat, for example, will attempt to place those mummies in the context of their coffins or other relevant materials, to give something of an overview of the individual pharaohs. In addition, a number of museums are taking advantage of non-invasive imaging techniques to reconstruct what individuals may have looked like, which should remind us of the humanity that underlies the mummified remains.

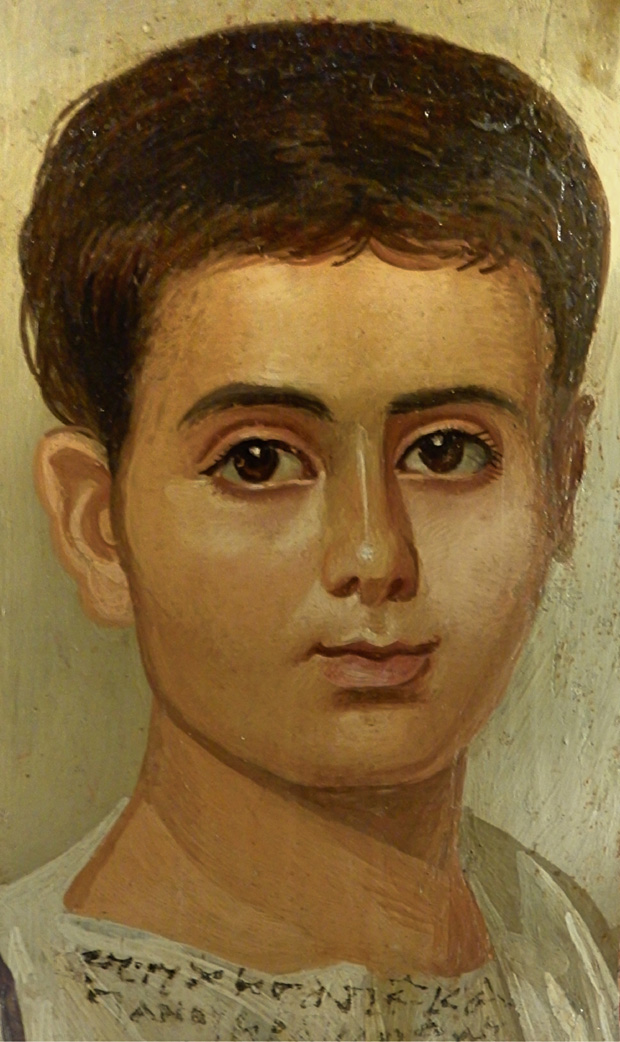

In the later period of Egyptian antiquity, nowhere is the connection to the living individual more vividly portrayed, however, than in the images that first began to emerge from Egypt in the 1880s, and which are grouped together loosely under the title ‘Fayum portraits’ (exquisitely illustrated in Doxiadis: The Mysterious Fayum Portraits).

These stunning images—some of which were most probably painted from life—are unusual, in that, at their best, they are naturalistic portraits in the Greek (Alexandrian) style, attached to Egyptian mummies, and from the Roman period (and with Roman hairstyles).

The Fayum portraits are now to be found in museums all around the world in Egyptian, Greco-Roman or Coptic collections, and, perhaps, give us the closest connection to the ‘personality’ of the owners to be found anywhere in antiquity.

‘Fayum’ mummy portrait of the Boy, Eutyches, in the Metropolitan Museum, New York City (Courtesy: Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

‘Fayum’ mummy portrait of the Boy, Eutyches, in the Metropolitan Museum, New York City (Courtesy: Nigel Fletcher-Jones)[/caption]

For the most part, though, we are dependent on science to give up us some insight into the personality and lives of ancient individuals, based on their desiccated, and desecrated, remains.

Increasingly archaeologists combine techniques—including computerized tomography (CT) scanning, 3D printing, Egyptology and art—in order to glimpse an ancient life. The University of Melbourne’s Meritamun Project Team, for example, recently announced an arresting example of this collaborative approach. Based on what might be regarded as rather unpromising material—a mummified head of unknown provenance.

The face that has emerged from the mass of tightly wound bandages, oils, and embalming materials is a striking portrait of a high status ancient Egyptian woman aged between 18 and 24 years old, perhaps dating to the Greco-Roman period, perhaps considerably older.

Facial reconstruction of ‘Meritamun’ (Courtesy: The University of Melbourne’s Meritamun Project (particularly Jennifer Mann, forensic sculptor & Paul Burston, photographer).[/caption]

Facial reconstruction of ‘Meritamun’ (Courtesy: The University of Melbourne’s Meritamun Project (particularly Jennifer Mann, forensic sculptor & Paul Burston, photographer).[/caption]

It is reasonable to assume that the young lady had a sweet tooth, as her teeth show significant signs of tooth decay, and the team detected two tooth abscesses, which, if they had become infected, may have her killed her. Other evidence from the bones suggests that she was also anemic, which may have been the result of contracting malaria. This may have hastened her untimely end.

With regard to the royal mummies themselves, it is surprising that any of these individual’s remains have survived at all. None, apart from Tutankhamen, were discovered in their original state of eternal repose. We know from court records that at the end of the 20th dynasty the last resting places of pharaohs were a target for tomb robbers.

So great was the problem that priests of the 21st and 22nd dynasties (roughly the period between 1100BC and 700BC) transferred many of the royal mummies from their tombs to hidden places of relative safety. We know certainly of two such caches, one at Deir al-Bahari and one found within the tomb of Amenhotep II in the Valley of the Kings, and there may be others that are still to be found.

The main intention of the priests, it seems, was specifically to preserve the bodies of the kings, and a lack of associated objects, together with other disturbances of the caches, has led to some confusion in identifying some of the mummies. However, the identifiable bodies of some of the greatest pharaohs—Thutmose III, Seti I and Ramesses II—were amongst those found together in Deir al-Bahari, and the bodies of Amenhotep II, Thutmose IV, and Ramesses III, were amongst those found in the tomb of Amenhotep II.

These royal mummies have also been studied in recent years by using CT scans, and the results so far have been recently expertly described in Scanning The Pharaohs: CT Imaging of the New Kingdom Royal Mummies by Zahi Hawass and Sahar Saleem.

For me, it is the little details of this study that give us a human insight which are important.

If the identification of one of the female mummies (KV60 A) as Hatshepsut is correct, it is likely that she stood around 159cm tall, and died when she was around 60 years old. Based on her obesity and the very poor state of her teeth, she may very well have died from complications relating to diabetes. Sadly, it is as likely that she died from cancer, which had spread to her bones.

As another fascinating example, the end of the reign of Ramesses III was marked by widespread famine, and an economic crisis in Egypt. So bad did the situation become that we know there was an assassination attempt on the life of the pharaoh, but it has been the subject of debate whether that attempt was successful or not. What the CT scans of the mummy suggest is that the assassination was successful. All the structures of the neck had been severed in what must have been a fatal cut from a dagger.

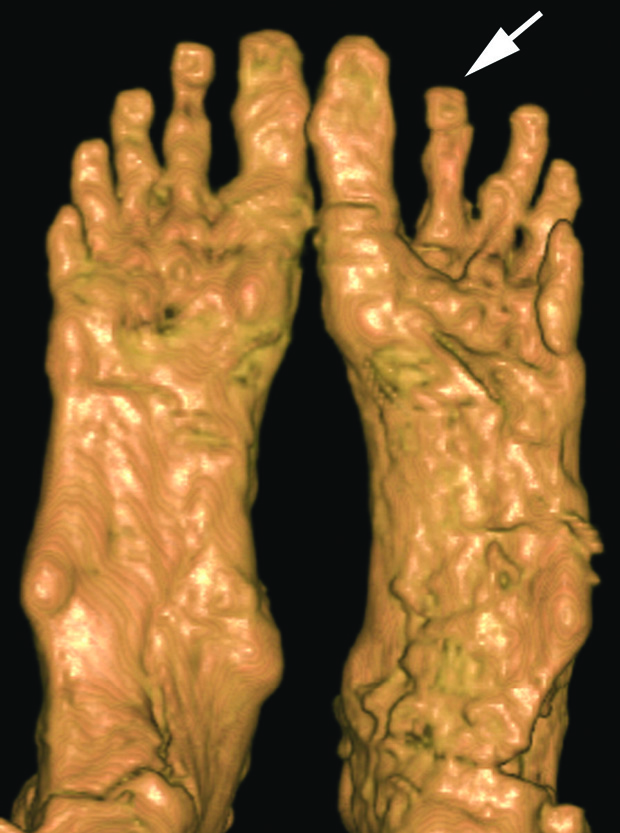

Most poignantly of all, reexamination of the mummy of Tutankhamun, which had remained undisturbed until 1925, confirmed his death at around 19 years old, possibly as a result of complications arising from a broken leg. The CT scans confirmed that the ‘boy king’ was probably born with a clubbed left foot which probably caused him pain throughout his short life, and helps to explain why so many walking sticks were found in his tomb.

3D CT scan of Tutankhamun’s feet showing the left foot deformity, from below (from Hawass & Saleem: Scanning the Pharaohs)[/caption]

3D CT scan of Tutankhamun’s feet showing the left foot deformity, from below (from Hawass & Saleem: Scanning the Pharaohs)[/caption]

All of these emerging details about the lives of individuals will hopefully instil in children something other than discomfort when they meet a mummy. We should make every effort to help them see a person, but that is a story for next month…

(With special thanks to the University of Melbourne’s Meritamun Project Team: Dr Ryan Jefferies, Jennifer Mann, Dr Janet Davey, Dr Varsha Pilbrow, Gavan Mitchell, Stacey Gorski, and Paul Burston.)

Nigel Fletcher-Jones is director of the American University in Cairo Press. Join Nigel on Facebook and browse AUC's list of stores at aucpress.com.

Comments

Leave a Comment