The recent killing of Cecil the Lion in Zimbabwe has thrust the thorny issue of big game hunting in the international public eye.

By Richard Hoath

The lion is iconic and enigmatic. It was worshipped by the Ancient Egyptians as the goddess Sekhmet, consort of Ptah, and dubbed “Great Lady, beloved of Ptah, holy one, powerful one.” It was held in similar reverence in ancient Sumeria, associated with the great king Gilgamesh of the city of Uruk. It appears in Coptic iconography: the two lions burying Saint Paul in the vastness of the Eastern Desert. The controversial King Richard the Lion Heart is universally known as just that or as Qalb al-Assad or Coeur de Lion. And in modern culture we have Aslan in The Chronicles of Narnia and, slightly less eruditely, we have it Disneyfied as The Lion King. We have lions. And now we have Cecil.

For anyone having vacated the planet Earth this summer, Cecil was a 13-year old (that will become important) male lion who lived in the Hwange Park in Zimbabwe, Southern Africa. He was in his prime. He was fully maned and magnificent and, especially important given Zimbabwe’s basket case economy, a tourist magnet. But he was also collared and radio-tagged, part of a longstanding research project carried out by Oxford University under the leadership of the highly respected Dr. David Macdonald, founder of that university’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit. Cecil was probably the most known and studied lion in the world. And then in July this year he was shot.

He was shot by an American dentist, Walter Palmer, and that much is not disputed. The details are very much disputed. The price for Cecil’s head was reportedly $55,000. As a resident of the Hwange National Park, he was fully protected but he was reportedly lured out of the Park’s boundaries by the dentist’s “guides” and hence became fair game. He was shot by crossbow, not rifle, and reportedly took 40 hours to succumb to his wounds (this is supposedly “purist” hunting). His radio collar was subsequently later found hidden in a tree and his head had been severed for the ultimate prize — the trophy head.

When the news broke, photos of Cecil in his magnificent prime went global and viral. Over 550,000 clamored to sign a petition demanding the extradition of the dentist to Zimbabwe to face trial. His “guides” have already been arrested and the trial awaits. His slaughter has opened huge questions about the truths of big game hunting in Africa.

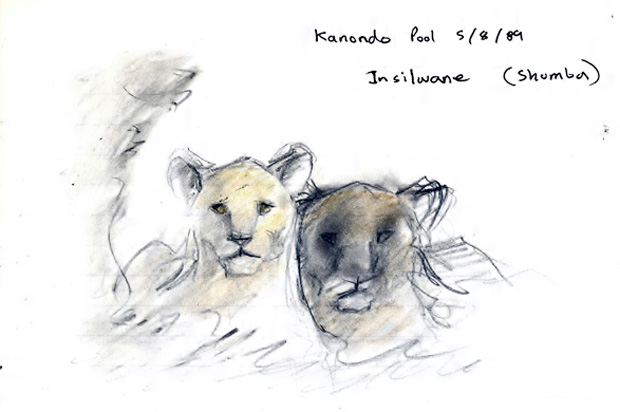

I was as upset as any of those petitioners about the demise of Cecil and it was ever so slightly personal. In 1989, specifically on the August 5, 1989, I was in the Hwange Park and I was on a game drive. I saw lions and in a day that also saw a cornucopia of wildlife from Common Bushbuck to Coqui Francolin the lions stood out and I watched them and made notes and I sketched. One of those lions, and those I sketched were all females or cubs, may well have been Cecil’s grandmother (remember Cecil was 13 and this was 1989).

[caption id="attachment_340956" align="alignnone" width="620"] One of these lions sketched by the author in 1989 may well have been Cecil's grandmother.[/caption]

One of these lions sketched by the author in 1989 may well have been Cecil's grandmother.[/caption]

The simplistic and emotive argument is that hunting, as in killing another creature for “sport,” is simply bad. But there is another side to the debate and one that I find deeply disturbing. I simply cannot get into the head, and do not want to get into the head, of anyone who can have an animal, any animal, not just a “magnificent” animal like Cecil or indeed any other lion, and pull the trigger, whether that be of a crossbow or a rifle. Sadly Cecil’s demise revealed that hunting, big game hunting, in sub-Saharan Africa is big business and there are powerful economic arguments for it.

In January 2014 the Dallas Safari Club in Texas held an auction. The prize was not a weekend at a spa resort to Gouna or an all expense-paid Nile cruise with a complimentary Pharaonic fancy dress party. The prize was the permit to shoot an endangered Black Rhino in Namibia. It was completely legal and the auction was made with the full agreement, and legal agreement, of the Namibian authorities. The winning bid was made by a Texan, Corey Knowlton, and while it is unclear whether the hunt has been made, as of March this year he has been given a permit by the USA Fish and Wildlife Service to import the trophy once the kill has been made.

Mr. Knowlton paid $350,000 at the auction to kill the rhino. The Black Rhino is one of the most endangered large mammals on Earth, having gone from a population of over 100,000 in the 1960s to less than 3,000 in the wild by the late 1980s. It is now almost entirely confined to very heavily protected National Parks and reserves in a very few African countries. Namibia has a population estimated at 1,500, probably one-third of the world’s remaining population. The rhino bought by Mr. Knowles is an old male, no longer capable of breeding, a potential threat, so the authorities argue, to younger rhinos within his territory and a rhino that, in his twilight years, will be destined to a prolonged and perhaps uncomfortable and painful death in his semi-desert habitat. The auction means that this lingering demise can be quickly and painlessly ended (assuming it is not a dentist’s “pure” hunt) and there will be $350,000 that can be ploughed back into Namibia’s conservation efforts as promised.

Sadly I can swallow that argument and that is what profoundly disturbs me. Namibia has a very sound conservation record — I have been there and the parks and reserves are superb. But by no means everywhere has that same network and authority and the opening up of such schemes on a larger scale is deeply questionable. And once again I just cannot get into the head of anyone who, when having the head of a Black Rhino, or a Cecil or indeed any other beast wants to pull a trigger rather than take a photo. I know — I have had Black Rhinos in my camera lens on several very, very precious occasions.

It is not a debate that is particularly relevant to Egypt. There is very little left here to hunt. Scimitar-horned Oryx and Addax are completely extinct, the Slender- horned Gazelle very rare and the Dorcas Gazelle and Nubian Ibex now very much depleted. The Wadi Gimal Protectorate in the southern Eastern Desert provides a refuge for the former and the St. Katherine’s Protectorate in South Sinai a haven for the latter.

This was not always the case. In Wadi Rish Rash, a deeply incised scar in the mountains of the Eastern Desert between Cairo and Beni Suef, there is a crumbling desert villa that was once a hunting lodge used by King Farouk. There is a small grove of palms and a garden still irrigated and with olives and oleanders. The cliffs that tower over the site are home to breeding Sooty Falin cons and to the Golden Spiny Mouse, a small rodent as golden and spiny as its name and unlike most of its murine relatives, active by day. This is no mice and man story, though. King Farouk’s lodge was a base from which to hunt the Nubian Ibex. To the west and north of his villa is a side wadi that can be negotiated through a long and winding trail. There is then an abrupt stop and a real clamber over cliff and scree. At the base of this bluff are a number of rusting and pitted metal rings embedded in the cliff. It was here that the mules were hitched as the hunters advanced.

For what happened next, visit Manial Palace on Rhoda Island. The trophy room there is a testament to the mammal fauna that Egypt once had. Other countries still have the opportunity to preserve that fauna. Economics say hunting may be part of it. As a naturalist who does not want to get inside a hunter’s head, I hope that is not the case.

Comments

Leave a Comment