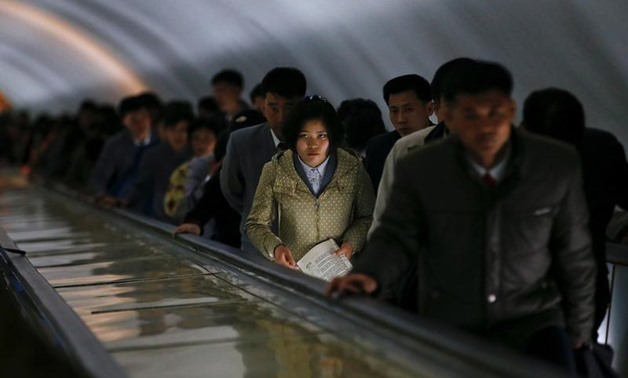

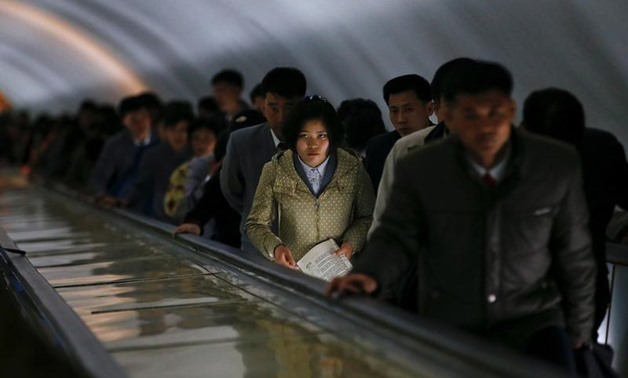

FILE PHOTO: People travel on escalators to exit a subway station in central Pyongyang, North Korea April 14, 2017. REUTERS/Damir Sagolj

DANDONG, China – 13 September 2017: The United Nations may have failed to slow North Korea’s weapons programs, but the country’s economy is already showing signs it is feeling the squeeze from the ongoing clampdown on trade, including a curb on fuel sales by China.

The latest sanctions agreed on Monday by the UN Security Council ban the export of textiles from North Korea, one of its few substantial foreign currency earners. They also capped imports of oil and refined products, without imposing the full ban the United States had sought.

Chinese traders along the border with North Korea and some regular visitors to the isolated country said scarcer and costlier fuel, as well as earlier UN sanctions banning the export of commodities such as seafood and coal, are now taking a toll.

“Our factory in North Korea is about to go bankrupt,” said an ethnically-Korean Chinese businessman in Dandong who sells cars refurbished at a factory in North Korea. He declined to be identified due to the sensitivity of the situation.

“If they can’t pay us, we’re not going to give them goods for free,” he said, referring to his North Korean customers.

A trader at another auto-related businesses in Dandong said cross-border trade had been hurt over the past few years, which he attributed to sanctions and less access to petrol. Several Chinese traders told Reuters the sanctions had stymied North Korean businesses’ ability to raise hard currency to trade.

“Last month sales were really bad, I only sold a couple of vehicles,” said the Chinese trader who sells new trucks, vans and minibuses to North Korea. “In August last year, I sold tens of vehicles and I thought that was bad.”

On top of the sanctions, some traders said Chinese officials have stepped up efforts to curb smuggling across the border, a key source of fuel in the northern parts of North Korea.

And Chinese bank branches in the northeast have curtailed doing business with North Koreans, according to branch staff.

FUEL PRICES SURGE

Still, North Korea has made strides in increasing its economic independence and not all traders or observers agreed the international pressure was having a major economic impact.

Many residents, long accustomed to restrictions and shortages, were most concerned about the risk of already tight fuel supplies being cut further, said Kang Mi-jin, a North Korean defector in Seoul who reports for the Daily NK website.

“If the U.S. were to say they plan to bomb Pyongyang, North Koreans wouldn’t care less. But if China says they are considering slashing oil exports to North Korea because of missile or nuclear tests, North Koreans would absolutely freak out,” she said.

Reuters reported in late June that state-run China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC) had suspended sales of gasoline and fuel to North Korea over concerns it would not get paid, and Chinese customs data showed that gasoline exports to the North had dropped 97 percent from a year earlier.

Petrol and diesel prices in North Korea surged after the cut and have almost doubled since late last year. In early September, petrol cost an average of $1.73/kg, compared with 97 cents last December, according to data from the defector-run Daily NK.

“The cost of living has gone up, the price of petrol has risen and there are fewer cars on the streets,” a foreign resident of the North Korean capital told Reuters. The only thing that had become cheaper was coal, he said, after China banned North Korean coal imports earlier this year.

Some of the scarcity of oil products and higher prices may have been caused by hoarding in anticipation of a clampdown on supply.

North Korea canceled an air show scheduled for this month in the coastal city of Wonsan, citing “current geopolitical circumstances”. Several Chinese traders said they believed it was because the military is saving aviation fuel.

The new UN resolution imposes a ban on condensates and natural gas liquids, a cap of 2 million barrels a year on refined petroleum products, and a cap on crude oil exports to North Korea at current levels.

OIL NOT BOMBS

North Korea uses far less crude than during its industrial heyday in the 1970s and 1980s, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. After cut-price supplies from China and the Soviet Union ended following the Cold War, consumption dropped from 76,000 barrels per day in 1991 to an estimated 15,000 last year, according to the EIA.

The use of small-scale solar has become widespread in the North, with many apartment balconies dotted with panels providing power for cooking and lighting.

China has not disclosed crude exports to North Korea for several years but industry sources say it supplies about 520,000 tonnes of crude a year to North Korea through an aging pipeline.

The pipeline already operates at the minimum level for which the waxy crude from China’s Daqing oil fields can flow without clogging, according to a senior oil industry source.

Chun Yung-woo, a former South Korean envoy on the North Korean nuclear issue, said the North could endure for a year or two without oil imports.

“North Koreans are so used to living in harsh economic conditions that they would just get by for at least one year even if the oil ban is adopted, rationing the existing stockpile among top elites at a minimum level and replacing cars, tractors, equipment with cow wagons, human labor etc,” he said.

“They would also manage to produce oil from whatever resources are available, whether it be coal, trees or plants.”

Comments

Leave a Comment