Millions of women worldwide have been deprived of the right to a proper education. Despite evident and notable progress to decrease illiteracy rates around the world, the problem is still prevalent and remains one of the principal issues in the way of achieving sustainable development in many countries, including Egypt.

According to the World’s Women 2015 report, published every five years, 781 million adults over the age of 15 are illiterate; more than 496 million of them (two thirds) are women. In Egypt alone, women and girls constitute 10,469,330 of the illiterate population, compared to 7,596,425 males.

A more recent study by the state’s statistics agency CAPMAS published in 2017 places illiteracy at 20.1 percent in Egypt, or 14.3 million individuals, with women forming 9.1 million of the total number. Women constitute almost 64 percent of the total number of Egyptians above the age 9 who can’t read or write.

Literacy rate in the Middle East and North Africa segregated by age group - source UNESCO

This month we shed the light on Egypt’s adult learning programs and how the General Authority for Adult Education has been catering to the hopes and needs of girls and women, giving access to essential schooling and learning at any age. Along the way, we came across some of the most inspirational women, of all ages, who have overcome social and economic challenges and life barriers to receive their well-deserved and needed education.

“I cannot express how much I love learning. I still remember how I cried my heart out when I was six years old when my father decided to prevent me from going to school. He said boys do not succeed in school; so how would girls? I got married at 19 and never allowed my kids to skip one day of school as their education was my life goal. When I turned 25, I enrolled in a literacy class at my kids’ school, I used to go with them and I obtained the literacy certificate. Now I am in preparatory school and I will continue to learn as there is no limit to education,” says Attiyat Mohammed, 55, enrolled in one of the General Authority for Adult Education (GAAE)’s literacy centers at El-Gamaleya neighborhood in Cairo.

A female adult learner enrolled at the General Authority for Adult Education (GAA) literacy program in El-Gamaleya, Cairo - Egypt Today, Yasmine Hassan

A female adult learner enrolled at the General Authority for Adult Education (GAA) literacy program in El-Gamaleya, Cairo - Egypt Today, Yasmine Hassan

Mohamed is one of 4,823,994 adult learners, of both sexes, who have been enrolled in literacy centers around Egypt during the last three years, according to GAAE. A total of 2,682,721 have been granted their literacy certificate and some of them have went on to pursue their graduate studies.

Access to quality education at any age is a basic human right guaranteed by all human rights treaties. The interest in universal education dates back to the World Declaration of Human Rights (1948), stating that primary education is free and compulsory for all children, taking into account quantitative and qualitative aspects of education. As the former UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan said in 2015, “without achieving gender equality for girls in education, the world has no chance of achieving many of the ambitious health, social and development targets it has set for itself.”

Egypt’s education reform efforts

As a member of the global community that has one of the largest education systems in the world, with more than 16 million students at different levels of education, Egypt has been keen to pursue reform efforts to improve the status of formal and informal education in the country for years. Hence, the Egyptian constitution of 2014 ensures the importance of education as an issue of national security and a basic right for all. It affirms that education is the vehicle for progress, development and prosperity. It also guarantees that education is free and compulsory until the end of the secondary stage or its equivalent.

In light of this commitment and to realize the full potential of the Egyptian population, Egypt developed a National Education Strategy (2014-2030) “Together We Can,” which pays special attention to adult learning, gender parity and school drop-outs, with the goal of achieving human development and modernizing the education system in Egypt through adopting an inclusive approach.

“Together We Can” introduces several innovative models, aiming to provide school drop-outs, youth and adult learners with the skills necessary to reintegrate into formal schools and to improve the educational services delivered by informal education. These models include the one-class schools, community and local schools, girls-friendly schools and literacy opportunities for disabled learners.

Egypt’s education reform efforts are guided by global agendas to promote equal accessibility to quality education for all people. These global agendas include the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), adopted in 2015, and feature a dedicated goal to education and lifelong learning that calls on countries to “ensure inclusive and quality education for all and promote lifelong learning;” as well as the goals of the global movement “Education for All (EFA)” launched in 2000 by UNESCO in coordination with the UNDP, UNFPA, UNICEF and the World Bank.

The General Authority for Adult Education: programs and goals

The concept of literacy and adult education has become more diversified to include kinds of education other than basic literacy. It has also become more advanced in terms of goals, content, methodologies, teaching and learning skills, monitoring of progress and evaluation of results. Widening the adult education concept and going beyond acquiring the basic literacy skills in Egypt allows for promoting critical thinking, tolerance and acceptance of others.

To further validate the current status of literacy and adult education in Egypt and the policies undertaken by the government or civil society to provide literacy education programs, we talked to the main actor in this field, the General Authority for Adult Education (GAAE). The GAAE was formally established in 1993 as an agency under the Cabinet of Ministers to open literacy centers across the country. The GAAE is the only provider of officially recognized literacy certification.

The GAAE defines the illiterate person, according to law number 31 of the year 2009, as “any citizen between the ages of 15-35 who is not registered in any formal school and does not know how to read, write or do arithmetic.” However, they still accept any person who would like to join the literacy programs even, if they are not in the targeted age group.

With a vision to create an environment where access to literacy programs is a valued right to everyone, the agency adopts annual implementation plans with specific objectives and targets to improve adult literacy in Egypt, mainly focusing on governorates with higher illiteracy rates. For the year 2017-2018, the GAAE plans to educate 2 million illiterate persons, whether as direct beneficiaries of their programs or through other national initiatives across the country.

“The authority’s representatives communicate with community leaders and influential figures like imams, mayors, businessmen and local council members or parliamentarians who are trusted by their communities to help us spread the word about the available programs and promote people’s enrollment,” Acting Chairperson of the GAAE Ahmed Hassan says.

In addition to its literacy centers, the GAAE supports any educational activities that take place within and outside the educational institutions for anyone who is not enrolled in formal education, had previously dropped out of school, or those who never had the chance to receive formal schooling due to social or economic reasons, or due to the failure of basic education systems to retain students.

The duration of the literacy programs ranges between three to six months, according to the educational level of the adult learner. The only rule to start a classroom is to adopt the GAAE official curriculum “Learn and be Enlightened.”

In cooperation with several partners, including the UNESCO, the agency developed 11 educational courses, responding to the actual needs of the learners, to complement the basic literacy curriculum. These courses include training for employment, life skills, human rights and health education—which attracts female learners the most. The GAAE also pays special attention to learners with disabilities; there are dedicated classes for the blind or visually impaired in Aswan, among other governorates.

Hassan adds that many individuals and organizations have contributed to adult literacy work in Egypt. The authority has signed more than 600 cooperation protocols with all relevant ministries and organizations, Hassan says, including the ministries of endowments, education, health, youth and sports. GAAE also cooperates with the Armed Forces, universities, mosques, women clubs and health clubs in all governorates to reach illiterates.

Moreover, the GAAE organizes regular information convoys to promote their literacy programs and raise awareness in every home, neighborhood, village, town and district. Once a classroom is established, people inform others about it; so the students are usually familiar with each other’s classes. “All classes are designed to fit the learners’ needs and address any barriers. We have classes that run in the evening so that the students can join after they finish their work,” Hassan explains.

All programs are free of charge, including the books, tests and certificates, which motivates the learners and makes it easier for them to seek education. Hassan also explains that there are some gender differences in the adult learners’ motivation; men and boys mainly enroll to obtain the certificate required for issuing some official documents, like a driving license or a passport, or to decrease the duration of compulsory service in the army. For women, they mostly participate in the literacy programs to be able to help their children with homework or to read the Quran, transportation and hospital signs, as well as reading subtitles of foreign movies and TV series. “I used to be scared of going out of the village because I cannot read the transportation signs. Now I even have the courage to go to Al-Attaba,” says Faten, who is enrolled at the GAAE literacy center in El-Badrasheen, Giza.

Adult Learners' literacy class in El-Badrasheen, Giza - Egypt Today, Yasmine Hassan

Adult Learners' literacy class in El-Badrasheen, Giza - Egypt Today, Yasmine Hassan

Adult learners can participate and voice their needs as well as the needs of their communities as they learn. Education provides people, especially women and girls, with the opportunity to exercise their civic participation rights and to have a role in the development of their community and the decision-making processes within their private life. “Reading and writing empowered me and improved my self-esteem. Now, I can write my full name and help my son with his homework. As I learn, I can voice the needs of my village and actively claim them,” says Sharbat Isamil, a woman enrolled in a literacy center in El-Badrasheen.

The GAAE focuses on promoting the concept of lifelong learning through raising awareness that obtaining the literacy certificate is the first step before continuing advanced studies and becoming public servants. Every year, the authority publishes a book titled From Illiteracy to University documenting success stories of learners who continued their studies after the literacy program.

Stories of success, empowerment and inspiration

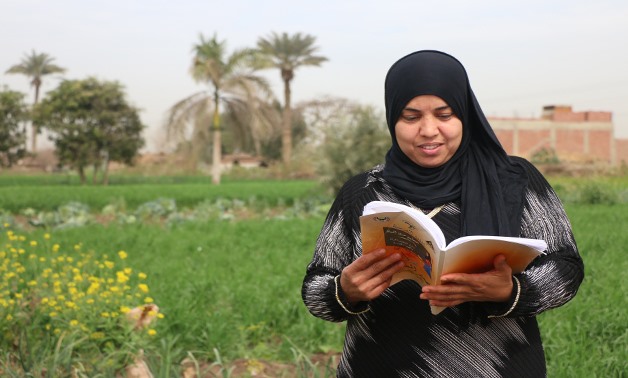

After exploring the programs and goals of GAAE, we were invited to visit two different classrooms; one in the countryside at El-Badrasheen, where women and girls sit in on the ground and take their class in an open area surrounded with farms and greener, and another urban classroom in El-Gamaleya, Cairo, where learners gather in rooms affiliated with the nearby Al-Salam mosque.

Each of the enrolled learners has a different story, but they all share the same motivation and inspirational dedication to pursue their education. They spoke to us about the difficulties and struggles they went through because of their illiteracy and their paths as they returned to education as adults.

Wafa Ahmed Ali, 50, is a student of El-Gamalya centre. She enrolled two years ago, passed the literacy level and is now in the second year of preparatory school.

“I wanted to learn to be able to communicate with my three children who are all at university. I also wanted to read the Quran and to use the internet. Now, I have a smartphone and I use applications like Facebook and Whatsapp to communicate with my friends,” Ali says.

Rania Ibrahim, 20, is a first-year student at the faculty of commerce; her ambition is to become a businesswoman. “Feeling neglected in the formal schooling system and the lack of attention or care from teachers were the main reasons why I dropped out of school in the third grade. In 2015, I joined the literacy center feeling scared and embarrassed. However, being surrounded by committed teachers and friendly colleagues helped me overcome these feelings,” Ibrahim says.

An iconic figure and the godmother of El-Gamaleya center is Laila Ismail. In 1997, she approached the GAAE to open the center and collected donations to build two classes on top of the mosque’s ablution or Wudu’ area. “When I started I only had one student, she was a woman. After one week, I had 41 students,” Ismail says.

To reach a wider group of people, Ismail cooperated with the imam to announce the program in the mosque. She also designed comics with messages highlighting the importance of literacy that she distributed after the Friday prayers.

“I organize open days in the neighborhood to attract people and introduce the program to them,” Ismail says. “I want to do something for my people; most of the students that I teach were forced to leave education and I want to help them.”

Ismail told us that she still has many ideas to develop the program. She wants to add a digital literacy component to teach learners how to use computers. She also suggested signing an official protocol with the mosque to guarantee that no one would ask them to leave the building.

The dynamo of both literacy centers were the teachers. All learners agreed that they were very supportive and understanding, and that they are always keen to make sure that everyone understands the lessons.

We met with Sabah Darwish, who was herself an adult learner at El-Gamaleya centre and is now a tutor. Darwish obtained her literacy certificate and finished her diploma despite never being admitted to school before. She teaches Arabic and arithmetic to literacy students. “When I enrolled in the literacy program, my life changed and I discovered that much information people used to tell me were false. Now I know how to look for any information I need.”

Khaled Ahmed is also a tutor at the center. He volunteers to teach English and Mathematics. “Education is like medicine. You have to prescribe the right medicine to the diagnosed disease, and that is how I deal with learners. I teach each one according to their needs,” Ahmed says.

He believes the only approach to eradicate illiteracy is to tackle the root causes of school dropouts, including the alleviated financial burdens of formal education and the consequences of private tutoring. Ahmed also capitalizes on raising awareness about the value of education. “The educational process needs to be developed in Egypt, because education is no less important than combating terrorism as it affects the whole country,” Ahmed says.

Such successful women illustrate an inspiring example of willpower and dedication to the key element of empowerment; that is, a person’s agency. They decided to improve their lives as individuals and to have a positive role in their communities through learning and fighting social stigmas. “We are still treated differently in universities and other [formal] institutions because we are literacy program graduates. They think that we are inferior, but my colleagues and I will challenge this perception and prove to the whole world that literacy program graduates, and especially girls, are smart and independent. We will succeed,” Ibrahim says.

Comments

Leave a Comment