February 22 is one of the two days people flock to witness one of Egypt’s greatest solar alignments when the sun’s rays filter through the 63-meter Great Hall of Abu Simbel to light and bless the Holy of Holies. It is a day to remember not only the great civilization that built such an intricate work of art and testament to advanced architecture, but also the great collaborative effort exerted in the 1960s to move the temple complex from its original location 200 meters to a new one on an artificial hill and safeguard it against being swept away by the Nile flood.

Fresh out of college, I was assigned by the government to go work near the borders of Sudan on the Abu Simbel project. I was ecstatic to receive the assignment, despite it meaning I would live in the middle of the desert for four years. It was a prestigious and interesting project with international experts; it was bound to give me tons of experience. The experience was an educational one, and it truly set my career off and opened many doors for me.

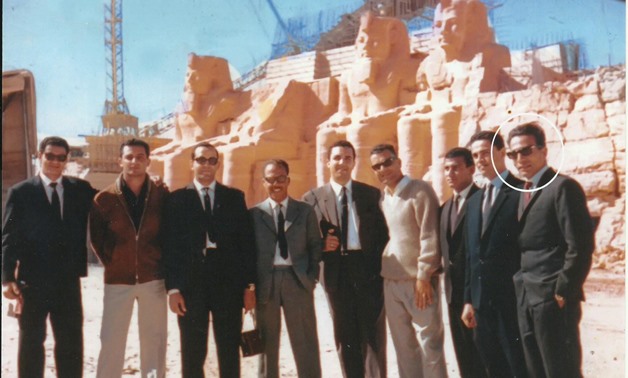

When we first got there, there was nothing but a temple and the desert. Initially, all us Egyptian engineers lived in a boathouse right next to that of the international engineers’, which really meant we all got close to one another and socialized all the time.

Shortly after, I was tasked with building the housing complex, which is now the Nefertari Hotel, in addition to my work at the temple. I would work from 8am to 2pm on construction work and then go back to the boathouse to finish paperwork.

The Abu Simbel temple complex is located in Nubia, 230 kilometers away from Aswan and dates back to 1244 BC. Only discovered in 1813, after being buried by sand, the temple complex was built by Ramsis II over the course of 20 years and consists of two massive rock temples. The complex is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of Nubia’s most important monuments.

After the Aswan High Dam was built, the Nile water level in this area continued to rise dangerously, posing a serious threat to the Nubia area, including the Abu Simbel temples. The UNESCO joined forces with Egypt and a team of international engineers from Germany, France, Italy, Sweden and Egypt to launch the ambitious project to relocate the Abu Simbel temples in November 1963, and successfully completed the mission in September 1968. Costing $40 million at the time, the international collaboration effort aimed to protect and safeguard one of the biggest historical monuments in the world.

The project to relocate and save the Abu Simbel temples was a complex and carefully designed one, with various details involved, and absolutely no room for mistakes or lack of planning. There is no doubt that building the High Dam in Aswan kept a lot of water behind the dam, and day after day, the water levels became higher and higher and would have eventually flooded the temples of Abu Simbel.

Salvaging Abu Simbel

Until a permanent solution was found to relocate the temples, a cofferdam was built around the two temples to protect them against the rising water levels. The 370-meter-wide dam was made of steel sheets that were filled from both sides and reached 27 meters in height. A pumping station and drainage were built to prevent any water from sweeping away the project area.

The complex is made of several rooms and halls that are filled with drawings and ornaments and that tell tales of victories achieved by Ramsis II, including his victory in the Battle of Kadesh. It is divided into two temples; the Great Temple is dedicated to the sun god Amun-Ra, Ptah and Ra Harakhte. The small temple is dedicated to the goddess Hathor and carries various depictions of his wife Nefertari.

The statue of Ramses the Great at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel is reassembled after having been moved in 1967 to save it from being flooded.

The statue of Ramses the Great at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel is reassembled after having been moved in 1967 to save it from being flooded.

The temple complex measures 63 meters in length from its entrance and all the way to the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctuary. Inside, two statues, that of Amun and Ramsis II, are illuminated on the sunrise of October 22 and February 22 of every year, but never on the other days, which shows intricate astrology and engineering knowledge of the time. Historians argue that these two dates most likely coincide with the king’s birthday and coronation day.

On the outside, four distinct 20-meter-high statues of Ramsis II and two of his wife, Nefertari, adorn the entrance and show the greatness of ancient Egyptian arts.

To start excavations to extract the two temples’ walls and ceilings from inside the mountain, we had to cover the entire facade with sand fills to protect them from any debris from the excavation process, then dig a tunnel for workers to enter and exit the site.

The temple’s roof was supported by steel scaffolding; and rubber sheets were placed to protect the inscribed blocks throughout the cutting process.

The excavation process was then carried out carefully from the top of the mountain using bulldozers. Before reaching the roof, engineers ensured workers used only electric jack hammers till they reached a depth of 80 centimeters, to cut the roof without any damage. At this point the workers had to be very careful in saving the pharaoh’s art by using sawing machines until they got to 70 centimeters of depth. The last 10 centimeters were cut with handy saws.

The entire 807 blocks of the Great Temple were re-cut and re-built in this manner, as were the 235 blocks of the Small Temple. Each block was duly numbered, and two pore holes were bored inside each block. Steel bars were fixed into the holes with epoxy before the blocks were carefully transferred by crane to a storage area.

The next stage was re-erecting the walls and roofs of the temples using reinforced concrete from the back, so visitors couldn’t see them once complete. Two domes were then built to cover the structure of the temple, which was a very clever idea to hold the construction. The thickness of the reinforced concrete dome was between 1.4 meters and 2.10 meters, and it measured 17 meters in depth. The foundation dome was 22 meters high and 60 meters in diameter. The dome is considered one of the strongest in the world because it is effectively carrying the great weight of the artificial hill, several layers of rubble and rock that were compacted together to form a mountain shape.

The statues of Ramsis II were then placed and the cutting lines were filled with chemical materials and powder mixed together with fine dust of the cutting blocks that were carefully chosen to give the exact original colour.

Complicated as it was, the most impressive thing about this salvage project, from the engineering point of view, remains the intricate calculations to achieve the original solar-alignment, something ancient engineers carefully designed to let the sun pass twice a year for 63.1 meters through the temple to illuminate Ramsis’s face on February 22 and October 22.

Life in the Camp

When my duties were done, it was time to socialize; I am a very sociable person and had very good relationships with my coworkers. I would arrange boat trips on Fridays for foreign and Egyptian engineers to go to Lake Nasser, which is beautiful. We also had a club on the premises and a swimming pool, so we spent our free time playing golf, table tennis, tennis and swimming. The social relationships we built there with Germans, Swedes, French and various other nationalities really made a difference in the experience and we kept in touch after the project was done.

But I did more than work and have fun; I was very active in the community and constantly making suggestions through the media to improve the area. I remember once working on a feature for Akher Saa magazine on Nubian weddings; but because all the workers on camp were men, and I wanted to stage a wedding for photography, I got some workers to pose as brides inside camel caravans.

Almost 50 years later, I was invited for an event by the UNESCO to celebrate our efforts. I went back to the site, and I was proud to see the work I have done remain intact throughout all those years. I also got to reunite with everyone I worked with; Egyptians and foreigners.

But overall, Abu Simbel was the project of a lifetime, and I still remember all the happy, difficult and rewarding moments I lived there.

Medhat Ibrahim is an architect and one of the consultant engineers who worked on the 1968 UNESCO-led project to relocate the Temple of Abu Simbel.

Comments

Leave a Comment