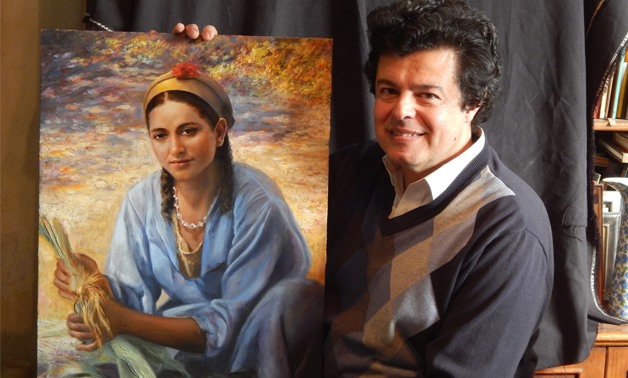

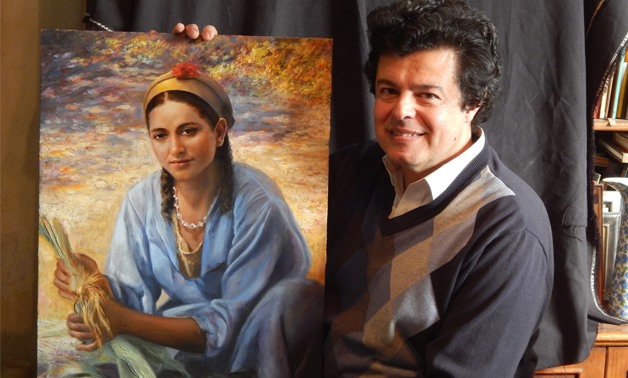

Farid Fadel with his 2017 painting. “Please, look at me with respect.” - Photo courtesy of Farid Fadel

It was “hanging day.” I took my artwork to the gallery in Garden City and was given permission to take down the paintings of the previous show. My largest work depicted the prophet Moses carrying the stone tablets. In the background is an imaginary Sinai that symbolizes many stations in his long life. It took pride of place on the central wall of the gallery. I was only 13 then and my mother looked at the painting signed and dated 1971, then turned to me and said, “Don’t sell that one Freddie, you will need it later for your retrospective.”

“Moses,” the first large painting from my 1971 exhibition, gouache on cardboard.

Now 46 years later, I still own the painting and have decided to show it in my first retrospective exhibition! I often think how lovingly strategic my mother had been and now my dear wife Mona continues to carry the torch. Since we married in 1988 she has been advising me to keep at least one painting from every exhibition as a memorable milestone of my artistic journey. “I don’t want you to beg collectors for your artwork once you decide to hold a retrospective show,” she said as she remembered how she had to do that for a Sabry Ragheb retrospective exhibition at AUC.

“Let the children live their childhood,” 2017

Though realism oozes out of most of my paintings, there is always a hidden message inside. A common one for all though is the essential role of beauty, harmony and balance. A quiet, warm sunset painting, inspired by a traditional Japanese tea ceremony, in Ain Sokhna depicts this theme quite clearly. I painted it. A second message, “Let the children live their childhood,” is another one featured in this collection and shows three girls happily swinging on primitive road swing. They are having a lot of fun with no need for modern gadgets and the like. I think they look much happier than many children today who cannot tear their eyes away from video games and mobile screens.

I take my hat off to working women in rural Egypt. They work all day long carrying heavy loads, raising children, preparing meals, baking bread, farming, selling at the local market and caring for livestock—and they often don’t hear a word of appreciation. I pay tribute to the heroic Egyptian woman in two paintings. A smiling woman is depicted in one painting shucking corncobs while in another we see a lady in red and yellow carrying freshly ground wheat, a vast green landscape in the background.

My story goes back to my early childhood. I started drawing in college at the tender age of three. It was more a need than a hobby, visual expression and communication became a real part of who I was. I drew everything that interested me, mostly from memory. When I was nine, my mother opened a new world for me as we went through her textbook The Story of Art by E. Gombrisch. I particularly loved the Renaissance period and at once started my first drawing of the Mona Lisa. A period of watercolors followed where I did my unfinished annunciation and several portraits and landscapes including a screaming self-portrait. My first two exhibitions in 1971 and 1972 were a true display of all my interests as an early teen. Many paintings were done using finger gel paint in an expressionistic free style. Upon the opening of my fifth exhibition in 1975, the head of the Egyptian Parliament recognized my talent and I was awarded a trip to Italy to experience Western art first hand. I stayed with a fellow artist at the Egyptian Academy in Rome and our neighbor downstairs was the famous painter Seif Wanly. We quickly developed a good friendship and exchanged our view on art as we made the museum rounds at Villa Borghese.

“The Unfinished Annunciation,” watercolor painted in 1970 (aged 8)

“Blessed are those who believe without seeing,” a message for Easter week 2017

Time constraints during my medical studies did not stop my artistic output—on the contrary, some of my medical student friends joined me in several art shows that we gave at Kasr al Aini’s faculty of medicine. During the 1980s I became more interested in portraiture, landscapes and still-life subjects. When I married, my wife became my muse, as did our two daughters Dalia and Lily.

The early 1990s saw the illustrations of New Testament stories; a five-year commitment with no exhibitions, but as my dear wife says, “a Bible is forever.” Now I have to bare my soul and share my vision. I believe beauty is an integral component of any creative expression. Some artists merely reflect the society in their works with its good and bad, but often it becomes pessimistic, horrible and ugly. Literary and performing arts may tackle a variety of controversial subjects, but then they are not with us 24/7. Plastic arts, however, have the privilege of a continuous presence therefore they carry a certain social responsibility coupled with aesthetic balance. In this way we can build a personal relationship with a painting or a piece of sculpture as it becomes a part of our environment, our home, our life.

In 1997 I distilled my thoughts in a short manifesto of what I called Aesthetic Integrated Naturalism (AIN). At a lecture at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio I argued that naturalism has always existed as an artistic undercurrent throughout human history. If art is not always synonymous with beauty, it is at least the legitimate channel to satisfy the aesthetic needs of humans. Yes, we are born with a need to look at and enjoy something beautiful. It is perhaps befitting that this retrospective collection of paintings should include a dozen paintings all done in 2017, each with a social/moral message.

One in particular took a lot of thought in its making. It depicts the exterior and the interior of a colorful Nubian House, separated by a crystal palm tree: “Let your inside be as good as your outside” is the message. The crystal palm tree symbolizes transparency which is essential to moral integrity. In the same way, my advice to my art students is: “Be yourself, don’t worry about finding a style, just be free, look inside, look outside, paint a lot and one day it will all come together, and your brush will be able to tell your story.”

Messages by Farid Fadel is now showing at the Salah Taher Gallery, Cairo Opera House, Zamalek • The exhibition will run through Thursday, April 20 • open daily from 10am to 2:30pm and from 4:30 to 8:30 pm except Fridays

Comments

Leave a Comment