Photograph by Richard Hoath

Thetford is a sleepy, small town in rural Norfolk in southeastern England. The railway takes you from London through the flat, fertile, verdancy of some of the country’s most productive farmland and somewhere, perhaps halfway between the great cathedral cities of Ely and Norwich, one alights at Thetford. And it was in Thetford I found myself this July and one might ask why.

Thetford is famed—probably a too big a word—as the birthplace of the English philosopher Thomas Paine and is also a rather good place to find a small brown bird called the Wood Lark. But over recent years in early July it has become the venue, courtesy of the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), for the Annual General Meeting of the Ornithological Society of the Middle-East (OSME). This year was no exception, and on the July 1, I found myself amongst the great and the good of Middle-Eastern bird study swapping anecdote and analysis and generally gorging on a bird-fest. Papers were delivered on migrating Bar-tailed Godwits from Oman to Siberia, on new migration bottlenecks in Azerbaijan and educational projects in Armenia. There was a sobering report on illegal bird killing over the Arabian Peninsula (Egypt was covered a few years back with damning results), and there was a review from BirdLife International on Important Bird Areas in the OSME region. All uplifting stuff for the specialist and I was duly uplifted.

But for me, the most important part of the meeting was the announcement and recognition of the publication of an Arabic version of Richard Porter and Simon Aspinall’s Birds of the Middle East. This has long been available in English, the second edition being published in 2010. What was missing for a region that is predominantly Arabic speaking was an Arabic translation. This is now available, beautifully illustrated in 176 color plates by some of the world’s foremost bird artists, courtesy of funding from such organizations as the Royal Society for Protection of Birds (RSPB), BirdLife International, OSME and others, and translated by Said Abdullah Mohammed.

Translators rarely get proper credit and it was fitting that Said was awarded for his work at the conference and was presented with the original painting for the cover of the book, a stunning pair of Blue-cheeked Bee-eaters.

The Arabic translation of the book is not yet—to my knowledge—available in Egypt, but can be ordered online at www.spnl.org/product/birds-of-the-middle-east-arabic-edition. Just a word of caution: While the title would indicate that Egypt is one of the countries covered, it does not fall within the region considered the Middle East by the authors whose remit stops at the borders with Israel, Saudi and Jordan. However, the vast majority of birds found here are covered in much more detail than any locally available guides, the exceptions largely being the African species that are increasingly being reported from the very south of Egypt’s mainland.

It seems odd that the Ornithological Society of the Middle East should hold its conference in rural England and perhaps that should be a matter of debate though the reasons are administrative and logistical. The meeting was made live over Facebook for the first time though and the morning session accumulated seven friends. Early days!

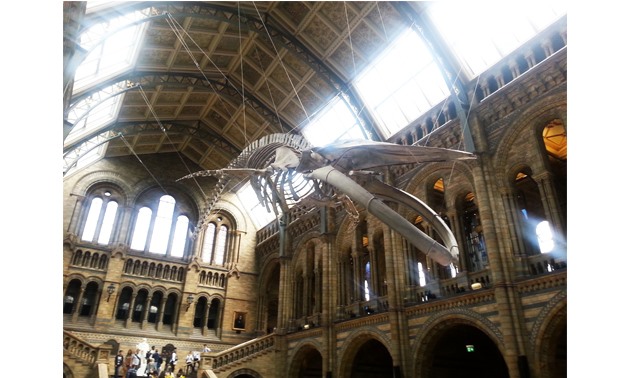

We used to hold our meetings in London at the Natural History Museum back in the 1990s, and it was to the Natural History Museum that I returned later last month. The museum is an icon of all things naturally historical and I can remember many inspirational trips as a schoolchild drinking in the vast galleries of natural memorabilia, of birds and animals that I never thought could exist but did; and that I then thought I would never see alive, but in many cases I have now thus seen. Since 1979 the immense opening hall of the museum has been dominated by a huge skeleton of a dinosaur, a Diplodocus to be precise, a vastly tall and extremely long creature (actually a plaster cast) that appealed to the wonder that every child has for dinosaurs and the wonder that in many of us our inner child retains. It was inspirational to many, myself included and part of my childhood. I used to be in thrall as I walked through the museum portals and found myself confronted with a once-living creature that simply defied even the most lively infant imagination.

The museum made the decision to take down the Diplodocus, fondly known to generations as Dippy, and replace it with another skeleton, this time of a blue whale, a skeleton that had languished for decades, since 1934, in the mammal section of the museum largely unnoticed and unloved. The rationale was straightforward. While the Diplodocus was awesomely proportioned and dramatic and filled the potential void of the museum’s breathtaking entrance, it was a fossil. It was of a dead creature, a creature from many millions of years ago whose demise had nothing to do with humans, but in all probability an asteroid impact.

The replacement, the blue whale named Hope, is the skeleton of the largest animal to have ever inhabited Earth. Blue whales can weigh nearly 200 tons and measure 30 meters in length (Hope’s skeleton comes in at just over 25 meters). They are still with us in the oceans but by the mid-twentieth century their population had crashed from around 230,000 to less than 14,000 due entirely to hunting by humans. Since the complete ban on whaling in 1979 further enforced in 1986, their population has stabilized in some areas or increased, but they are still critically endangered.

Hope was not killed by whalers. She was stranded off the coast of Ireland in 1891. She was purchased by an entrepreneur who sold her blubber for oil and her baleen for use as stays in ladies’ corsets. Her skeleton was sold to the Natural History Museum, and I can remember her being displayed stiff, straight and huge in one of the many side rooms on my early visits.

Now she is displayed as if in life, her huge back arched and the vast mouth open, a mouth whose lower mandible is the single largest bone in the animal kingdom—ever. The visitor is today greeted by this breathtaking display and one can only stand in awe. The message is clear. This magnificent animal was brought to the brink of extinction by man. It has now been brought back from that brink and stands testimony to our responsibility to the natural world. A whole new generation of visitors will be inspired. When I visited on July 14, the first day Hope was open to the public, people were walking in jaws agape by the spectacle and I hope the message.

The blue whale has never been certainly recorded from Egyptian waters. There is a possible record from Marsa Matrouh in 1892, but this more likely to have been a fin whale. A 20-meter fin whale in a highly-emaciated condition was washed up at the El Omayed Protected area in March 2010. Large whales are rare in Egyptian waters, so for most the best chance to see them is far in land at the excellent museum at Wadi El Hitan and in the surrounding desert. These skeletons may not sound inspiring but in a curious way they are. This is what the director of London’s Natural History Museum had to say about its new centerpiece. Speaking about Hope and the research that had been done in putting her in this dramatic new location he stated that “it is our hope for the future that we can use good science and good evidence to make the right kind of decisions about those big environmental issues.”

Tragically washed up on an Irish beach over 100 years ago Hope may be providing just what her name suggests to a new generation of custodians of this planet. There’s hope. et

Richard Hoath is a Senior Instructor at AUC’s Department of Rhetoric and Composition. He has published extensively about Egypt’s wildlife and fauna.

Comments

Leave a Comment