It may be time to revolutionize the language of death.

By Yasmine Nazmy

When a car bomb targeting Lebanon’s former financial minister exploded in downtown Beirut on December 27, 2013, seven people were killed, including the target, Mohammed Chatah, and his driver. The other five, who were not the target of the attacks, were merely ‘collateral damage,’ as they put it. One of those was Mohamed Chaar, a teenager who was enjoying a day out with his friends and just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. The last thing he did before he died was to take a selfie; a few minutes later, another photo was taken of his bloodied body as he lay dying. It was not long before Chaar was proclaimed a ‘martyr.’

The gurgling turmoil in the Middle East has made death a harsh reality, and, on each side of each conflict, there are martyrs. But in the case of Chaar, his friends and activists rejected his martyrdom. A group of bloggers, infuriated by the politicization of his death, insisted that he was not a martyr but rather a victim of senseless political violence. The group made their rejection public when they launched their #Notamartyr campaign on social media under the hashtag of the same name. They invite users to take their own selfies with placards stating the reasons why they refused to be labeled martyrs.

On their Facebook page, the group says:

“We are victims, not martyrs. We refuse to become martyrs. We refuse to remain victims. We refuse to die a collateral death.

“We are angry, sad and frustrated with the current situation in our country. But we are not hopeless.

“And we have dreams for our country.

“We know we are not alone.”

They invited contributors to share their own thoughts on life, death and martyrdom. Some of the messages included:

“I don’t want to survive. I want to live.”“I don’t want to wish I was born in a different country anymore.”

“I don’t want to keep saying nothing will ever change.”

“I don’t want to be scared of my country; I don’t want to be scared in my country.”

“I don’t want my own future to be determined by other individual’s beliefs and decisions.”

“I want to live for my children, not die for my country.”

Hitting Close to Home

The campaign will strike a chord with anyone who is uneasy with the politicization of death in Egypt. In the past three years, it seems that anyone who died in political violence in Egypt has become a martyr — including innocent bystanders like Chaar, who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Over 900 people killed in protests in 2011 are martyrs; police officers and soldiers killed on duty are martyrs; football fans killed in the Port Said Stadium massacre are martyrs.

But the playing field is not level: Government officials honor some martyrs and not others. Revolutionaries claim as their own those who have died fighting against the regime but rarely name those who have been killed doing their duty to it.

In the past weeks, as bombs claim the lives of bystanders, soldiers and police officers, and protesters are killed in clashes with police, more people have been martyred. Whether their deaths occur when they are on duty or off-duty, whether they are collateral or incidental, whether they set out from home with the knowledge that they might very well die, they are all considered martyrs. For many, martyrs are those who sacrificed their lives to keep the spirit of revolution and the belief in a brighter future alive. For others, martyrs are those who did their duty and stood their ground when their country was under attack.

In all cases, blood was spilled and families grieved the loss of loved ones; those who could, did leverage their deaths. Leveraging the sanctity and honor attributed martyrdom, politicians, the military, the police and the media have used it as a tool to garner sympathy for their causes and gain legitimacy.

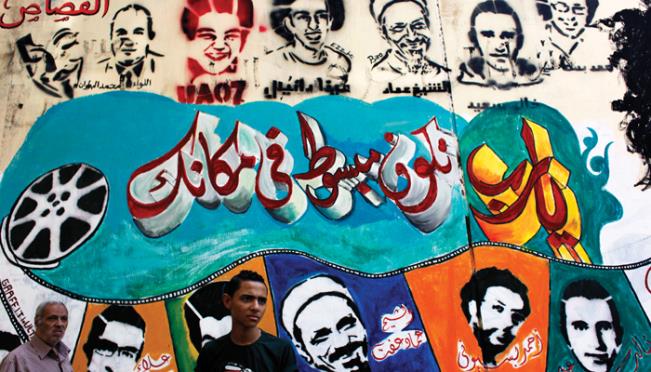

For revolutionaries, the memory of martyrs has been essential to appropriating the revolution. Murals of those martyred in protest have been painted over time and again; faces have been printed on flags and raised high during marches; lists of names have been circulated to document and remind those who would rather forget that many have died in the name of the revolution.

But does calling them martyrs make them more or less worthy of our indignation? Our sympathy? Does it serve as a palliative, or a reminder that justice is absent? What does it say of power, to say that someone has been murdered and another has been martyred? What of the martyrs who were simply ‘collateral’? How does it affect our psyche when we speak of the accountability of those who colluded, oversaw, planned or turned a blind eye to their deaths? If they were murdered, would the justice system be keener to punish the perpetrators? Does martyrdom fuel the revolution and the need for change in a positive way? By romanticizing death, does it somehow pave the way for more death?

As for their families, does believing that their children were martyred rather than murdered help them make any sense out of otherwise senseless deaths? Does martyrdom give more value to death than to life? And how can we strip those in power from using death to manipulate others?

Perhaps we can learn something from the Lebanese campaign. For generations, Lebanon has been a hotbed of senseless murders, many of which are ‘collateral.’ Civil wars, sectarian violence and political violence have made it necessary to re-appropriate the language of power and re-examine how death is used as a political tool. It is unlikely that we will see anything similar to the #Notamartyr campaign in Egypt soon, but it does raise questions that perhaps we need to ask ourselves about who benefits from murder and martyrdom. It may be useful to re-examine how politicizing death paves the way for memory to be manipulated.

Maybe if we disown the religious undertones of martyrdom and claim the reality of their murder, we will be more committed to seeking justice for their loss. Perhaps we will rob politicians who use death to rally support the ability to do so. Perhaps we will deny them the ability to sit idly by while the dead are counted and buried.

It may be well worth pondering the words of one of the #Notamartyr contributors: “I do not want to survive, I want to live.” et

Comments

Leave a Comment