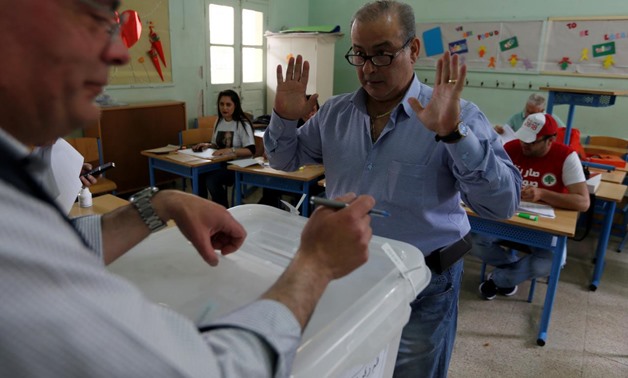

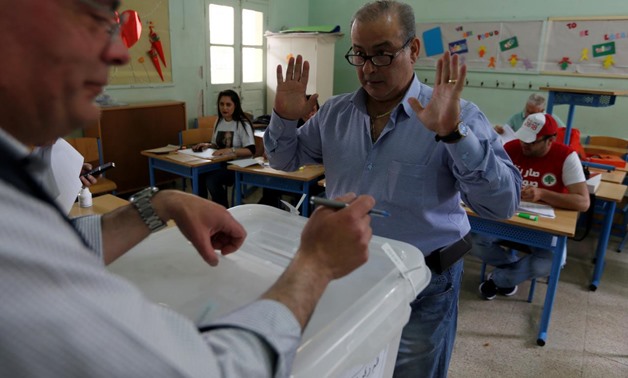

A man gestures after casting his vote at a polling station during the parliamentary election in Beirut, Lebanon, May 6, 2018 - REUTERS/Jamal Saidi

CAIRO - 6 May 2018: The next in a wave of elections across the Middle East began today in Lebanon, as people take to the polls in the long-awaited parliamentary election. Nine years have passed since the last election, however the election is not expected to upset the apple cart and alter the prevailing balance of power. According to

, “Most experts agree that it’s already possible to accurately predict the outcomes of about two-thirds of the 128 seats.” Money and clientelism are, once again, playing a decisive role.

The last parliamentary elections to take place in the country occurred in 2009, for what was supposed to be a four-year term. However, much changed in the region during those four years. Uprising, revolution and war have caused much instability across the region. While Lebanon has fared well considering the catastrophic war in neighboring Syria, parliament has twice extended its term in order to address security concerns and reform the country’s electoral laws.

Voting is scheduled to continue for 12 hours, with the polls opening at 7 a.m. (6 a.m. CLT). Across the country 3.8 million registered voters are expected to cast their ballot amongst 6,800 polling stations, with in excess of 700,000 voters heading to the polls for the first time.

The election results will begin to emerge overnight, with the formal result expected in the coming days. As per the election law, forecasts and predictions of how the parties are expected to fare will not be published while the polls remain open; they will close at 7 p.m. (6 p.m. CLT).

The new electoral law introduced a list-based system of proportional representation, which is intended to more accurately represent Lebanon’s complex demographics, and the election will see 583 candidates compete for the 128 seats in the Lebanese Parliament. The number of districts has been reduced, and expatriates are being allowed to vote for the first time.

Nevertheless, the confessional political system in Lebanon remains the same: parliament seats are divided evenly between Muslims and Christians, the president must always be a Maronite, the prime minister a Sunni and the speaker of parliament a Shiite.

A total of 976 candidates originally registered to run, however the final list cut this to 583 candidates. In a promising sign of equality and acceptance, 86 female candidates are competing for the 128 seats; an amazing feat considering women currently make up just three percent of parliament, and only 12 women stood in the 2009 election.

Lebanon’s Election in Context:

Following the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in February 2005, two alliances have shaped the political waters in Lebanon. The arguably pro-western “March 14” bloc and the Hezbollah-led “March 8” bloc have dominated politics in the country for the past 13 years in an often violent rivalry which has drawn foreign powers into the fray. The election on March 6 is expected to be the first political showdown in nine years, and the waters are not as clear as they once were.

A portrait of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri hangs above a crowded street in central Beirut on May 4, 2018, ahead of Sunday's first legislative elections in nine years - AFP/Joseph Eid

A portrait of Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri hangs above a crowded street in central Beirut on May 4, 2018, ahead of Sunday's first legislative elections in nine years - AFP/Joseph Eid

Saad Hariri, the leader of the Future Movement party since 2005 and the figurehead of the March 14 alliance, returned to Lebanon after a three year self-imposed exile in 2014. After the collapse of his first government in 2011 – when Hezbollah and its allies resigned from government while Hariri posed for pictures with President Barack Obama in the Oval Office – Hariri managed to form a new government in late 2016.

Hariri found favor with a political adversary, the Hezbollah-allied strongman Michel Aoun’s Free Patriotic Movement, and Aoun assumed the office of the Presidency in late 2016. Aoun, the Lebanese Army General from 1984 and short-term prime minster from 1988-1990, returned to Lebanon in 2005 following the assassination of Rafik Hariri and days after the withdrawal of Syrian troops from the country. As head of the Free Patriotic Movement, he signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Hezbollah in 2006, which resulted in a major alliance that has remained ever since. The Free Patriotic Movement is the largest party in the March 8 alliance.

The war in Syria seems to have complicated the balance of power in Syria. With memories of Lebanon’s disastrous 15 year civil war, and with contemporary evidence around the region, Hariri’s Future Movement and its allies in the March 14 alliance favor Lebanon as a non-confrontational and non-intervening state.

Yet Hezbollah's influential military role in Assad’s likely forthcoming victory in Syria has challenged internal stability and disrupted the stability of the March 14 bloc.

Saudi Arabia, a key ally of the West, has supported the March 14 alliance as a counter measure to Iran’s growing regional influence in which Hezbollah plays a crucial role. However this relationship has been tarnished.

In a bizarre tale of events, Hariri was summoned to Saudi Arabia late last year, reportedly detained on Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s (MBS) orders, and forced to issue his resignation from the Kingdom. Saudi fears of Iranian influence in Lebanon were being realized.

However, following a meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron, and once back on home soil in Lebanon, Hariri announced he was suspending his resignation in a move which seemed to bring relative stability to the country. Maybe Saudi-Hariri trust has been restored, maybe not, but last month Hariri and MBS appeared in a widely shared selfie together.

Lebanon remains a deeply divided and sectarian country, where a plethora of fragile alliances are on the verge of breaking and spilling open. While issues with the confessional system remain, regional conflicts are extenuating internal, sectarian tensions.

“Contrary to what many are accustomed to think, one thing limiting the possibility of change through the democratic process in Lebanon is not the existing sectarian electoral or political system. Rather, it is the sectarian political choices of average voters,”

Bashshar Haidar, Professor of Philosophy at the American University of Beirut.

What is expected in this election is that little will change. Faces may chance, but the prevailing forces behind the faces will not. Business as usual? Most likely, yes. Hezbollah’s power is expected to be bolstered through popular support, coercion and brute force. But as in any election, unpredictability prevails.

Comments

Leave a Comment