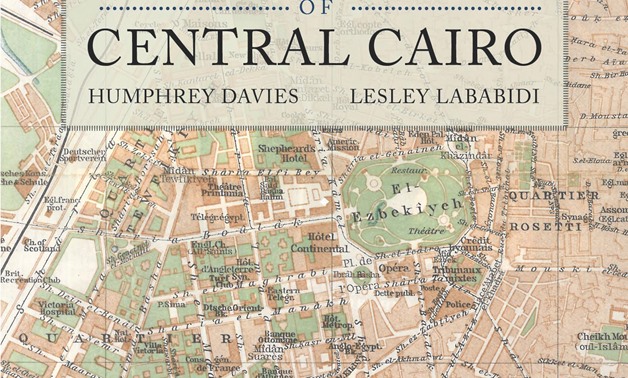

''A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo'' book cover.

CAIRO - 7 November 2018: Distinguished translator Humphrey Davies and acclaimed travel writer Leslie Lababidi explore Cairo’s streets to bring readers the story behind the names of each street.

As we go through life, we visit numerous streets and develop special attachments to some, if not all, of them.

Whether we are aware of it or not, streets are essential to the fabric of our lives. They are central to most of our memories; whether it’s the street where we went to school, or the one we once visited with a lover as our hands intertwined, or where our grandparents might have lived.

For many of us, our past, present, and our most defining memories are, in one way or another, attached to street names.

In A Field Guide to the Street Names of Central Cairo, recently published by the American University in Cairo Press, long-time Cairo residents and authors Humphrey Davies and Lesley Lababidi take the reader on an amusing and informative journey through the tales behind Cairo’s street names.

The product of almost two years of meticulous on-the-ground research, untold hours of digging through two hundred years of maps, as well as tracing and retracing streets deep into the crevices of Cairo’s districts, The Field Guide incorporates current streets and alleyways that were part of the Greater Ismailia area, from Bab el-Hadid in the north to Bab el-Luq in the east, Fumm el-Khalig in the south and Zamalek in the west.

Describing how he has always thought of Cairo’s street names as a living presence that evokes powerful memories, scenes, and atmospheres, Davies recounts,“I found it necessary, in the hopes of quieting some of these restless spirits, to try to pin down the reasons why which each was given its name.

” He further explains that the city’s street names are a kaleidoscope of its development, its history as the country’s capital, and the imagination of its inhabitants - since most streets are named by people while the authorities play catch-up.

“Names appear and disappear, sometimes in the same place, other times somewhere quite different.

They refuse, like the city, to stay still,’’ explains Davies, a Cambridge-educated translator of Arabic literature with 25 books under his belt, including translations of novels by Naguib Mahfouz and Elias Khoury.

Since maps play a critical role in telling the story of a city, the co-authors started by studying maps starting from the 1860s and through to the 1970s, to correlate changes over time.

“We also recognized inconsistencies between maps, which were clues that brought forward more questions to help piece together the puzzle,’’ says Labadidi, an avid traveller and writer of various unique travel volumes published by AUC Press.

The duo first compiled the names of every street within a district, visiting each and taking photographs of street signs; the research to recreate the story of a street then began at a later stage. Historically, distinct social and cultural attributes were clear of areas where the wealthy resided in comparison to the local of the working class.

Drawing from history, politics, economics, religion and society, the book provides an unparalleled account of the city’s urban history by looking deeper into the streets’ names and their history.

“A reader who lives in or visits the city might, if he has a trace of imagination, ask himself, ‘Who exactly was Yusef el-Gindi to have a street named after him, why is today’s Emad el-Din Street nowhere near that obscure (but powerful) Sufi sheikh’s tomb [after whom it was named], or why does the 12th-century scholar el-Qadi el-Fadel have no fewer than five [streets](count them!) named after him? This book scratches that itch,’’ Davies explains.

Although the book was initially Davies’ vision, according to Lababidi, each of the authors brought a set of unique skills and talents to the team.

Speaking of the partnership with Lababidi, Davies recounts, ‘’We both did a bit of everything, but Lesley brought to the team—in addition to her boundless energy and tenacity—a car and redoubtable driver, with which she criss-crossed the city, while I handled the Arabic material from the comfort of my apartment.”

Meanwhile, Lababidi explains that working with Davies was “a rare opportunity” at the overlap of her passion for people and history.

“When Humphrey invited me for coffee to discuss his ideas and vision, I was captivated,” Lababidi recalls. “I knew that this project would be groundbreaking and I wanted to be a part of it.”

Recalling how she was in awe of her counterpart’s depth of literary and linguistic understanding in the English and Arabic languages, Labadidi makes note of how critical Davies’ vast knowledge of Arabic was to the project, as he deciphered spelling or variations in words.

‘’How many times did we review a seemingly unimportant detail to get the exact story? Untold times! It was Humphrey’s insistence on fact-checking and perseverance that I overwhelmingly respect,’’ she says. The Field Guide is the first of its kind in both Arabic and English languages, although Fathi Hafiz al-Hadidi has written somewhat similar works.

As they worked on The Field Guide, Davies and Labadidi came across a number of interesting stories, such as an account of a teen millionaire who grew up in Bab el-Luq and was shot dead by his French wife at London’s Savoy Hotel in 1923, in front of the concierge, and a Sufi saint whose reputation for foolishness was exploited by Muhammad Ali Pasha.

“There is also the man who advanced the science of aviation by watching Cairo’s once ubiquitous, now vanished, birds of carrion and died a pauper there, believing that flying machines would bring world peace,” Davies recalls.

To Labadidi, the most interesting street names are related to lifestyle influences and events, such as Share’ el-Saha (Enclosure Street), named after a donkey market and Share’ Suq el-Asr (Afternoon Market Street), now renamed Share’ Rushdi.

There’s also Share’ el-Saqqayin (Water Sellers’ Street), named after the men who sold water wholesale in the street, carrying the load with skins they often transported on the backs of donkeys or camels.

Other street names, such as Share’ Ahmad Nabil or Share’ EshaqYaqub often gave little clue to their initial history, Labadidi says, adding that it took a great deal of digging up to uncover the forgotten war heroes who inspired street names. One special street, however, was the authors’ number one mystery for two years.

Lababidi recounts that they turned over every stone, looking for the story of Share’ Dubreih, now renamed as Share’ Seliman el-Halabi in the district of Tawfiqiya, before one fine day, Davies finally discovered Dubreih’s identity.

Apparently a French family name, it is unclear from the spelling whether it refers to a Dubray, a Debray, or even a Dupré. An obscure 19th-century biographical work seems to provide part of the answer. A “Yusef Dubreih” (the name appears only in Arabic) was the son of a doctor who came to Egypt with Clot Bey.

The family appears to have settled here and Yousef, who was born in Egypt, struggled at first to make ends meet in commerce and as an interpreter (for de Lesseps, among others), in which capacity he eventually joined the police. Remaining loyal to Khedive Tawfiq in the face of Urabi’s uprising, he was appointed, in a meteoric rise, director of the ministry of the interior and organized the country’s first secret police force.

It seems somehow fitting, therefore, that the name of the street which we believe bears his name (probably because he lived there) should have come to be so shrouded in mystery.

Humphrey Davies is a translator into English of Arabic literature, both old and new. With a PhD in Near East Studies from the University of California, Berkeley, he worked for many years with community development and grant-making organizations in the Arab World.

His first translation (Naguib Mahfouz’s Thebes at War) was published in 2003, his most recent is Elias Khoury’s Children of the Ghetto: My Name is Adam (forthcoming). He has lived in Cairo since 1997.

Lesley Lababidi documents visual and material culture and Egyptian traditional crafts. Since the summer of 2017, she has travelled the Silk Road from China through Central Asia, researching the migration of traditional and material craft techniques and the fluidity of cultural migration between Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

She is author of Cairo’s Street Stories: Exploring the City’s Statues, Squares, Bridges, Gardens, and Sidewalk Cafés (AUC Press, 2008); Cairo: The Family Guide (AUC Press, 2010. 4th ed.); Silent No More (AUC Press, 2001); and Cairo, The Practical Guide (AUC Press, 2011, 17th ed.), among others.

Comments

Leave a Comment